There's an essential paradox to being a writer, at least for a lot of people. It's supposed to be our job to understand what other people's lives are like--to empathize with everyone, and find the common humanity in a diverse range of characters. At the same time, many of us are hermetic, ingrown little weenies who just want everyone to go away.

Well--maybe we're not quite that bad. But most of us are fairly private people, and like a little silence, a little solitude, and a little detachment from the rat race. With a few notable exceptions, most of us are not personally adventurous--making up experiences is often as satisfying as, sometimes more satisfying than, actually having them. Furthermore, a lot of writers are educated people, and a lot of educated people come from the middle and upper classes (and again, there are lots of exceptions), and end up breathing fairly rarefied air their whole lives. Though my own family has run the gamut from factory work to finance, and my home town was largely down on its luck, I still pretty much reside in this category. I work at a college and live in a nice neighborhood, and most of my friends are college graduates with good jobs.

But it is my responsibility as an artist to try to see through this stuff, and understand both the universality of human emotion and, simultaneously, the diverse specificity of life as it's actually lived. And this is a challenge.

Lately, most of my contact with people outside my social sphere has come from...eBay and Craigslist. Funny as this sounds, my hobby--writing and recording music--cuts across the whole social spectrum, and when I find an instrument I'm interested in, it often leads me to glimpses of lives I might not otherwise have seen. I bought a crappy old Yamaha guitar from an African family who, against the odds, found themelves shivering in upstate New York; and a tube amp and lap steel from, believe it or not, an eighty-year-old Judeo-Christian mail-order preacher (he reminisced about sitting in on C&W dance parties at the grange hall back when there was such a thing, and learning to wire his home's electricity from a now-defunct trade school for Jewish youths); and a combo organ from a pawnshop in Rochester where, less than a mile from one the finest collections of art photography in the northeast, guys shaking with DT's at nine in the morning were lined up waiting to cash in on pocketsful of stolen wristwatches. The people who sold me a reel-to-reel tape deck last week were a jolly couple from Jersey for whom it is routine to buy four tractor-trailers full of rusting audio gear from a defunct music store and hawk it to total strangers on the internet for a living.

Needless to say, these are not especially impressive excursions outside the social comfort zone. But they're enough to remind me that not everyone is a blogger or college professor, that the possibilities for living are infinite, and infinitely interesting. Yeah, I already knew that, but it's all too easy to forget what you know.

What do you do to get out of the bubble, if in fact you're in one?

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

Elizabeth McCracken Will Have a Memoir

According to that New York Times blog.

I love Here's Your Hat, What's Your Hurry and The Giant's House (haven't read her other novel because it's about comedians, which shouldn't be a reason, but there you are) but somehow I never thought of McCracken as the memoiring kind. Maybe because when I met her, having invited her out to Montana to read (I think), I couldn't squeeze any info out of her at all. She was quiet, mysterious, and discreet. She gave the impression she had been raised in a castle on the Isle of Skye by former trapeze artists, or something, but didn't find it interesting enough to talk about.

Very much looking forward to An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination.

I love Here's Your Hat, What's Your Hurry and The Giant's House (haven't read her other novel because it's about comedians, which shouldn't be a reason, but there you are) but somehow I never thought of McCracken as the memoiring kind. Maybe because when I met her, having invited her out to Montana to read (I think), I couldn't squeeze any info out of her at all. She was quiet, mysterious, and discreet. She gave the impression she had been raised in a castle on the Isle of Skye by former trapeze artists, or something, but didn't find it interesting enough to talk about.

Very much looking forward to An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination.

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Offending Your Family

This morning I found myself sitting in the lobby of a Ramada Inn in Syracuse. (For any audio geeks reading this board, I had managed to find a Studer B67 on eBay and agreed to meet the sellers there to pick it up. A delightful mini-adventure it turns out. But I digress. (But then again, this blog is just one digression after another, so I retract that semi-apology.)) I picked up a copy of the local free weekly from the glass-and-fake-oak coffee table, opened it to the arts section, and found this:

Now, I am not here to get on Michael A. FitzGerald's case, as I know from long experience that there is nothing like a local paper to make you sound like a complete moron. I once gave an interview--set up, I'm afraid, by my mom--for my home town paper, and the resulting article did not contain a single thing I even remotely said. It was all entirely made up, from start to finish.

However, let me say that I think this imagine-your-friends-are dead tactic is ill-conceived in the extreme. FitzGerald, I should say, turns out to have just been worried about all the sex stuff in his book, and his mother getting grossed out by it. Fair enough; he's off the hook. But I've heard this argument made before, by writers whose aim is to fictionalize actual people in their lives, insulting the living crap out of them in the name of art.

There are plenty of books out there, really good ones, that feature thinly veiled versions of real people; and there are plenty of these real people who have gotten good and pissed over it. Ulysses, which I was praising here the other day, is a perfect example: Joyce didn't even bother changing the names of the people he slandered. He caught a bit of hell for this, and as I see it, he should have. I don't think he ought to have done it--it's shitty form. There's an argument to be made that Joyce had special license, because he was a genius, and what, Lennon, would you rather he hadn't written Ulysses? Huh? But that argument doesn't do it for me. Joyce does not deserve special consideration. If he was such a goddam genius--and he was, of course--he should have made people up instead. Ulysses might have been even better.

I guess what irks me about this topic is the idea that, in writing, the ends ought to justify the means; and in my view they never do. When you insult real people in a book, you're no better than a kid pissing off the highway overpass. You are alone, insulated by time and distance, and don't need to face the accused.

Now, here's where I admit that I've done exactly this. One of my novels contains a rather extended bit of revenge against one of my high school teachers, whose fictional doppelgager even has the same name, except with the letters slightly rearranged. It's a good bit, too, at least by my own standards--but to be entirely honest, I cringe to think of it. If I was to be a real man about it, I would have driven back to my home town, showed up at the dude's door, and told him to his face how he made me feel that time, back in 1986, when he gave me a wedgie in front of honors English. (Could I have had him fired by week's end? You bet. But I had not yet developed my antiauthoritarian chops. In fact, I suspect that was the day I got started on them.) That bit of my book might have been fun to write, but it's a small stain on my work, and a small tear in my moral fiber.

In any event, I don't think it's excuseable to rake real people over the coals in fiction--unless it's, like, the President, and you're a satirist. I also don't think it's an artistic compromise to curb one's impulse to do this. The fiction writer ought to process experience, to chew it up and spit it out in another form, not to prop it up and slap a coat of paint over it. To defy the vengeful instinct is to strengthen your mettle. Invention is power.

According to Michael A. FitzGerald, a Boise, Idaho-based author originally from Skaneateles, while he or she is writing, an author should pretend that everybody he knows is dead. This way, he'll never feel the need to censor his words or ideas out of concern for what friends or family might think.

Now, I am not here to get on Michael A. FitzGerald's case, as I know from long experience that there is nothing like a local paper to make you sound like a complete moron. I once gave an interview--set up, I'm afraid, by my mom--for my home town paper, and the resulting article did not contain a single thing I even remotely said. It was all entirely made up, from start to finish.

However, let me say that I think this imagine-your-friends-are dead tactic is ill-conceived in the extreme. FitzGerald, I should say, turns out to have just been worried about all the sex stuff in his book, and his mother getting grossed out by it. Fair enough; he's off the hook. But I've heard this argument made before, by writers whose aim is to fictionalize actual people in their lives, insulting the living crap out of them in the name of art.

There are plenty of books out there, really good ones, that feature thinly veiled versions of real people; and there are plenty of these real people who have gotten good and pissed over it. Ulysses, which I was praising here the other day, is a perfect example: Joyce didn't even bother changing the names of the people he slandered. He caught a bit of hell for this, and as I see it, he should have. I don't think he ought to have done it--it's shitty form. There's an argument to be made that Joyce had special license, because he was a genius, and what, Lennon, would you rather he hadn't written Ulysses? Huh? But that argument doesn't do it for me. Joyce does not deserve special consideration. If he was such a goddam genius--and he was, of course--he should have made people up instead. Ulysses might have been even better.

I guess what irks me about this topic is the idea that, in writing, the ends ought to justify the means; and in my view they never do. When you insult real people in a book, you're no better than a kid pissing off the highway overpass. You are alone, insulated by time and distance, and don't need to face the accused.

Now, here's where I admit that I've done exactly this. One of my novels contains a rather extended bit of revenge against one of my high school teachers, whose fictional doppelgager even has the same name, except with the letters slightly rearranged. It's a good bit, too, at least by my own standards--but to be entirely honest, I cringe to think of it. If I was to be a real man about it, I would have driven back to my home town, showed up at the dude's door, and told him to his face how he made me feel that time, back in 1986, when he gave me a wedgie in front of honors English. (Could I have had him fired by week's end? You bet. But I had not yet developed my antiauthoritarian chops. In fact, I suspect that was the day I got started on them.) That bit of my book might have been fun to write, but it's a small stain on my work, and a small tear in my moral fiber.

In any event, I don't think it's excuseable to rake real people over the coals in fiction--unless it's, like, the President, and you're a satirist. I also don't think it's an artistic compromise to curb one's impulse to do this. The fiction writer ought to process experience, to chew it up and spit it out in another form, not to prop it up and slap a coat of paint over it. To defy the vengeful instinct is to strengthen your mettle. Invention is power.

Saturday, October 27, 2007

Do Writing Classes Work?

I'm taking a writing class right now, for the first time in a zillion years. Okay, twelve. It's terrific fun, even though it's pretty mellow as writing classes go and aimed more at generating material than the usual thing, which is tearing other writers to shreds. Ha ha, I joke! Also, it's taught by my friend, and that puts a strange spin on things.

There is an oft-mumbled idea in the literary world that the problem with fiction today, and particularly with the short story, is writing workshops. Writing workshops, the popular wisdom says, make all writing the same -- they beat the originality out of people's work and reward unambitious mediocrity and pretentiousness.

How true is this? I don't know. It's hard to tell what the larger dynamic is when you're so caught up in the thing, and my experience of MFA school was intense and wonderful. I think about the writers in my classes and their work, and I honestly don't feel as if I, or anyone else, attempted to beat the originality out of them. But of course I don't feel that way! I wouldn't.

One of the most original writers in my classes then was (the beautiful and talented) Andrew Sean Greer. I remember grappling hard with his writing -- it was different and brilliant and sometimes difficult, partly because he wrote so damn much of it. I recall being quite critical of some small stuff: point of view changes in particular, and places where I thought he was being deliberately confusing. And enough time has passed for me to realize that part of my criticism had its roots in jealousy. But in those days we didn't think much of being supportive and encouraging in class; all that was for after class at the bar. I wonder if Andy felt as if his originality was being challenged, though? In any event, he's a great writer today, so we didn't do too much damage.

And I know that the criticism I received of my own work was, if anything, painfully legitimate.

So I can't argue that writing classes, in my limited experience, bring the quality of writing down -- I just never saw it. But do they help? And if so, how, and how much? This is harder. I often wonder what kind of writers I and JRL and our friends would be without those two years, and it is just impossible to say. I do know that we got at least as much out of our fellow students as out of the teachers, and probably more out of reading the work of others than we got from being read. In other words, it wasn't school that made the experience what it was, so much as the collection of incredible individuals we found there. Even more important was the two years of time and focus. Who ever gets that, in real life?

Another of the strongest and most geniusy writers I know, Brian Hall, never went to graduate school and as far as I know, never took a writing class. In fact, it's hard to imagine him in one.

You know what those workshops do? Suddenly I get it: they give people a chance to try out being a writer. Lots of people who get an MFA would have quit writing if they didn't get into a program -- lots of people wouldn't write at all without a class. And so, perhaps, the world is a bit overstocked in writers, and that's where the sense that writing workshops somehow bring the quality of writing down comes from. If it weren't for this plethora of classes, the only writers would be the Brian Hall type: self-taught, self-motivated geniuses who don't need the feedback, don't need the support system, don't even need the two years of free time.

There is an oft-mumbled idea in the literary world that the problem with fiction today, and particularly with the short story, is writing workshops. Writing workshops, the popular wisdom says, make all writing the same -- they beat the originality out of people's work and reward unambitious mediocrity and pretentiousness.

How true is this? I don't know. It's hard to tell what the larger dynamic is when you're so caught up in the thing, and my experience of MFA school was intense and wonderful. I think about the writers in my classes and their work, and I honestly don't feel as if I, or anyone else, attempted to beat the originality out of them. But of course I don't feel that way! I wouldn't.

One of the most original writers in my classes then was (the beautiful and talented) Andrew Sean Greer. I remember grappling hard with his writing -- it was different and brilliant and sometimes difficult, partly because he wrote so damn much of it. I recall being quite critical of some small stuff: point of view changes in particular, and places where I thought he was being deliberately confusing. And enough time has passed for me to realize that part of my criticism had its roots in jealousy. But in those days we didn't think much of being supportive and encouraging in class; all that was for after class at the bar. I wonder if Andy felt as if his originality was being challenged, though? In any event, he's a great writer today, so we didn't do too much damage.

And I know that the criticism I received of my own work was, if anything, painfully legitimate.

So I can't argue that writing classes, in my limited experience, bring the quality of writing down -- I just never saw it. But do they help? And if so, how, and how much? This is harder. I often wonder what kind of writers I and JRL and our friends would be without those two years, and it is just impossible to say. I do know that we got at least as much out of our fellow students as out of the teachers, and probably more out of reading the work of others than we got from being read. In other words, it wasn't school that made the experience what it was, so much as the collection of incredible individuals we found there. Even more important was the two years of time and focus. Who ever gets that, in real life?

Another of the strongest and most geniusy writers I know, Brian Hall, never went to graduate school and as far as I know, never took a writing class. In fact, it's hard to imagine him in one.

You know what those workshops do? Suddenly I get it: they give people a chance to try out being a writer. Lots of people who get an MFA would have quit writing if they didn't get into a program -- lots of people wouldn't write at all without a class. And so, perhaps, the world is a bit overstocked in writers, and that's where the sense that writing workshops somehow bring the quality of writing down comes from. If it weren't for this plethora of classes, the only writers would be the Brian Hall type: self-taught, self-motivated geniuses who don't need the feedback, don't need the support system, don't even need the two years of free time.

Friday, October 26, 2007

"Recharging"

Ach, how I hate that metaphor, when it's applied to acts performed with the goal of revitalizing the creative drive. As though getting yourself to write something were analagous, in some way, to plugging in a cell phone overnight. But it's handy enough, I suppose, to have some shorthand for this mysterious process; it's different for everyone and impossible to qualify.

I just got back from New York, and generally a trip to the city serves, for me, as a major source of remojofication. But not this time, for some reason. I attended a lit thing, hung out with some rock and roll cronies, and had a generally fine time...but for some reason, the expected juicing did not arrive. Instead, I found myself thinking, as I walked through Union Square, Jesus Christ, the world is freaking packed with people, and I just pined for the sofa, a glass of wine, and a heist novel.

Where does creative energy come from? After ransacking the lumber room of the mind, day after day for a couple of decades, searching for some mislaid scrap of it, I still don't understand what it is I'm looking for, or how it is I've manage to find it, when I do find it. It is fickle stuff, as mysterious and elusive as Sasquatch, and indeed, sometimes the process of capturing it is akin to slogging through a rainforest, scanning the humus for footprints.

It's related to happiness, I guess, and to confidence, and to the acceptance of the self. But not all that closely. I'm feeling quite happy, confident, and self-accepting today, and I don't feel like writing shit. Rhian's been reading about Sylvia Plath (I suspect you'll be hearing more about her tomorrow), and it looks like she wrote some of her best stuff in the throes of misery, humiliation, and self-loathing.

Sometimes a change in the weather inspires me. Sometimes the eighth straight day of rain. Sometimes it's a good song, or a horrible song, or the suffering of others, or their joy. Sometimes I'm moved by jealousy, or fear. Or admiration, or lust. Something somebody says, or that I wished they'd said. None of it makes the slightest bit of sense. Today, even writing this blog post is an effort. Tomorrow I might knock out ten pages. (Not bloody likely though, I'm afraid.)

What gets your motor running? Or rather--what has gotten it running in the past? Because past performance, as I'm sure you're aware, is no guarantee of future success.

I just got back from New York, and generally a trip to the city serves, for me, as a major source of remojofication. But not this time, for some reason. I attended a lit thing, hung out with some rock and roll cronies, and had a generally fine time...but for some reason, the expected juicing did not arrive. Instead, I found myself thinking, as I walked through Union Square, Jesus Christ, the world is freaking packed with people, and I just pined for the sofa, a glass of wine, and a heist novel.

Where does creative energy come from? After ransacking the lumber room of the mind, day after day for a couple of decades, searching for some mislaid scrap of it, I still don't understand what it is I'm looking for, or how it is I've manage to find it, when I do find it. It is fickle stuff, as mysterious and elusive as Sasquatch, and indeed, sometimes the process of capturing it is akin to slogging through a rainforest, scanning the humus for footprints.

It's related to happiness, I guess, and to confidence, and to the acceptance of the self. But not all that closely. I'm feeling quite happy, confident, and self-accepting today, and I don't feel like writing shit. Rhian's been reading about Sylvia Plath (I suspect you'll be hearing more about her tomorrow), and it looks like she wrote some of her best stuff in the throes of misery, humiliation, and self-loathing.

Sometimes a change in the weather inspires me. Sometimes the eighth straight day of rain. Sometimes it's a good song, or a horrible song, or the suffering of others, or their joy. Sometimes I'm moved by jealousy, or fear. Or admiration, or lust. Something somebody says, or that I wished they'd said. None of it makes the slightest bit of sense. Today, even writing this blog post is an effort. Tomorrow I might knock out ten pages. (Not bloody likely though, I'm afraid.)

What gets your motor running? Or rather--what has gotten it running in the past? Because past performance, as I'm sure you're aware, is no guarantee of future success.

Thursday, October 25, 2007

Writers' Rooms

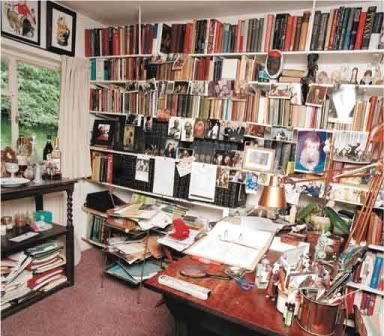

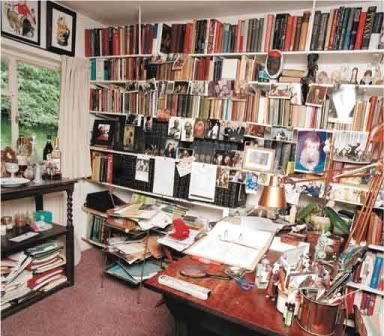

All right, this is the kind of writer-porn I officially disapprove of, but I admit that this collection of pictures of writers' work rooms on The Guardian Book page is somewhat fascinating (scroll down, in the bar on the right). I think John Mortimer's is the only room I could get any work done in:

See that little liquor shelf under the window? Quite an innovation. I also like all the postcards and goodies to look at, the brass desklamp, and the nice solid wooden desk.

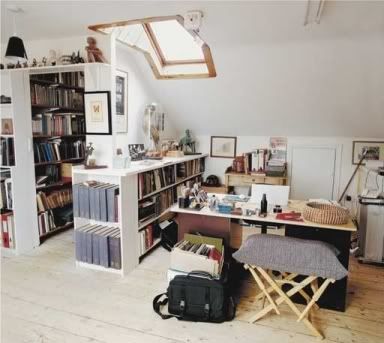

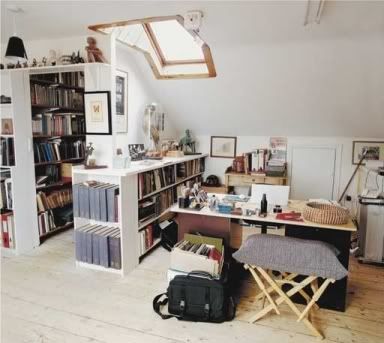

Here's Seamus Heaney's. A bit chilly, don't you think? Though I love the book stacks on the left:

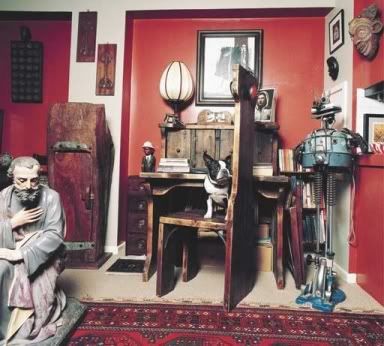

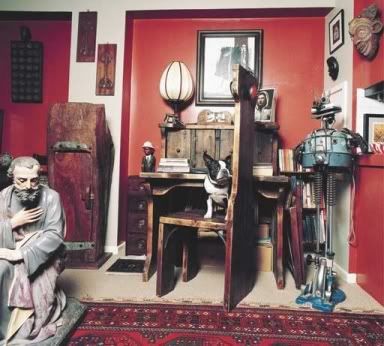

I'd have trouble working at Nicola Barker's place. I'd keep wondering how much I could get for all those knick-knacks on eBay:

I don't know Barker's work at all, but I'd guess that it's rather baroque.

I like a smallish room, I like to face a window, I like a heavy desk. I wonder if I'm trying to recreate my childhood bedroom, or maybe my college dorm room? A good room should allow your mind to leave it.

See that little liquor shelf under the window? Quite an innovation. I also like all the postcards and goodies to look at, the brass desklamp, and the nice solid wooden desk.

Here's Seamus Heaney's. A bit chilly, don't you think? Though I love the book stacks on the left:

I'd have trouble working at Nicola Barker's place. I'd keep wondering how much I could get for all those knick-knacks on eBay:

I don't know Barker's work at all, but I'd guess that it's rather baroque.

I like a smallish room, I like to face a window, I like a heavy desk. I wonder if I'm trying to recreate my childhood bedroom, or maybe my college dorm room? A good room should allow your mind to leave it.

Sunday, October 21, 2007

M-M-M-My Aesthetic

As a teacher of writing, I think I am getting a bit of a reputation for riding one particular hobby horse--the one where I tell students over and over to simplify and clarify their prose, to use as few words as possible to get their point across. One grad student out and out accused me of being totally biased against any kind of "beautiful" or "lyrical" writing.

And given my rhetoric, she had a point. I am generally suspicious of excessive elaboration--it usually has to prove its usefulness to me before I can accept it. If I had to say I had a particular aesthetic, it would be that of simple language expressing complex ideas. By "simple" I don't mean intentionally reductive or minimalist--I just mean no more than is necessary.

I think the exemplar of this aesthetic is probably Shakespeare, whose Comedy of Errors I read yesterday, and discussed today with the book group. It's not a major play, but it is highly entertaining and extraordinarily clever (two sets of twins, separated at birth, endure an afternoon of being mistaken for one another). It's also extremely straightforward in its language--anyone can understand it--yet musical to the ear. Perhaps most importantly, it harbors a lot of darkness and fear: the highly implausible plot has the threat of a beheading hanging over it, and the characters immerse themselves in marital disharmony, mental illness, political intrigue, and Christian philosophy. (Doug, the book group's retired pastor, had a lot to say about the influence on the play of Paul's Letter to the Ephesians.) Shakespeare is like a magician, who uses clear, fluid motions to do incredible and mysterious things.

But the thing about your personal aesthetic is, there's always something lying in wait to contradict it. Ulysses is perhaps the antithesis of my aesthetic--it's sprawling, pretentious, confusing, and stylistically inconsistent; it is the product of a supremely arrogant mind without the slightest concern for the comfort of its audience, in total opposition to Shakespeare's egalitarian appeal. And it ends with a big, gooey, overwritten and underpunctuated flourish involving buttocks ("plump mellow yellow smellow melons," in case you haven't had the pleasure).

And yet, I think Ulysses is freaking awesome. I think about it all the time, and it has surely influenced my work. I regard it as one of my twenty or so favorite novels, if you could even call it one. What's up with that?

Frankly, I have no idea. I could mutter something to you about containing multitudes, but I won't even bother. When it comes to art, it is not possible to appreciate too many different things. You can't stand Schoenberg until some string quartet or other makes you cry. You find pork chops repulsive until finally somebody cooks them right. You tell yourself your whole life that you're not into brunettes until suddenly you're married to one. Like Stephen Dedalus on the beach, taste is protean, and is to be assumed unstable at all times, and it's a good thing, too, because this means the world will never run out of stuff for you to love.

And given my rhetoric, she had a point. I am generally suspicious of excessive elaboration--it usually has to prove its usefulness to me before I can accept it. If I had to say I had a particular aesthetic, it would be that of simple language expressing complex ideas. By "simple" I don't mean intentionally reductive or minimalist--I just mean no more than is necessary.

I think the exemplar of this aesthetic is probably Shakespeare, whose Comedy of Errors I read yesterday, and discussed today with the book group. It's not a major play, but it is highly entertaining and extraordinarily clever (two sets of twins, separated at birth, endure an afternoon of being mistaken for one another). It's also extremely straightforward in its language--anyone can understand it--yet musical to the ear. Perhaps most importantly, it harbors a lot of darkness and fear: the highly implausible plot has the threat of a beheading hanging over it, and the characters immerse themselves in marital disharmony, mental illness, political intrigue, and Christian philosophy. (Doug, the book group's retired pastor, had a lot to say about the influence on the play of Paul's Letter to the Ephesians.) Shakespeare is like a magician, who uses clear, fluid motions to do incredible and mysterious things.

But the thing about your personal aesthetic is, there's always something lying in wait to contradict it. Ulysses is perhaps the antithesis of my aesthetic--it's sprawling, pretentious, confusing, and stylistically inconsistent; it is the product of a supremely arrogant mind without the slightest concern for the comfort of its audience, in total opposition to Shakespeare's egalitarian appeal. And it ends with a big, gooey, overwritten and underpunctuated flourish involving buttocks ("plump mellow yellow smellow melons," in case you haven't had the pleasure).

And yet, I think Ulysses is freaking awesome. I think about it all the time, and it has surely influenced my work. I regard it as one of my twenty or so favorite novels, if you could even call it one. What's up with that?

Frankly, I have no idea. I could mutter something to you about containing multitudes, but I won't even bother. When it comes to art, it is not possible to appreciate too many different things. You can't stand Schoenberg until some string quartet or other makes you cry. You find pork chops repulsive until finally somebody cooks them right. You tell yourself your whole life that you're not into brunettes until suddenly you're married to one. Like Stephen Dedalus on the beach, taste is protean, and is to be assumed unstable at all times, and it's a good thing, too, because this means the world will never run out of stuff for you to love.

Saturday, October 20, 2007

Banned Books

I know, I know, you were hoping for a post by JRL, but he's way behind on his book group Shakespeare so it's me again. This morning I set up a little Banned Books display (a little late to the party, since BB Week was in September) in the book store window, full of the usual: Huckleberry Finn, Harry Potter, In the Night Kitchen, etc. Minutes after I'd finished, a guy came marching in, asking, "So WHO tried banning Harry Potter??" Erm, I didn't know, so I had to Google it for him. Someone in Zeeland, Michigan, it turns out. Oh, also a lady in Pennsylvania. "Hmm," he said, before striding out again, umbrella beneath his arm. Perhaps he was disappointed that it wasn't George Bush, or the mayor of Ithaca.

It makes me wonder if maybe we're giving the overwrought, book-fearing loonies of the world a bit too much attention. Asking a school to remove a book because it shows a cartoon penis (as in the case with Sendak's In the Night Kitchen) maybe be ridiculous, galling, and even offensive, but it's hardly a human rights crime*. If a crazed librarian decided to stock my kids' school library with hard core porn and copies of Soldier of Fortune magazine, I might raise a teeny objection. Not every book is suitable for children, in fact, and it isn't surprising that not everyone agrees where the line is. My own mother once complained to my school about the book A Taste of Blackberries, in which a character is stung to death by bees, because I cried for a week after reading it (and still can't see the book today without feeling a bit queasy). I'm glad my poor mom never showed up on those lists.

The real problem, of course, is parents trying to impose their religious values onto public school systems. Such impositions should not be allowed to happen, and fortunately they rarely are. But the Banned Books discussion is not framed that way; instead, the misguided attempts to remove books with too much (or the wrong kind of) sex or witchcraft or swearing are described as violations of intellectual freedom. Perhaps they shouldn't be given so much credit.

The Cities of Refuge project (formerly Cities of Asylum) gives refuge to writers who really have been banned -- Ithaca is currently hosting Sarah Mkhonza, who was threatened and assaulted in her native Swaziland for criticizing the government in her newspaper columns. Iranian writer Reza Daneshvar, here from 2003 to 2006, was jailed for writing a novel about the 1953 coup. Other exiled writers are staying in Las Vegas, Pittsburgh, and Santa Fe. It would be a great thing if other cities followed suit and brought even more writers here to have some time and space to write freely.

*Anyway, there's an easy solution to the cartoon penis, as the librarian at my elementary school discovered: she cut out a tiny pair of paper undies and taped them onto the naked child in the school's copy of In the Night Kitchen.

It makes me wonder if maybe we're giving the overwrought, book-fearing loonies of the world a bit too much attention. Asking a school to remove a book because it shows a cartoon penis (as in the case with Sendak's In the Night Kitchen) maybe be ridiculous, galling, and even offensive, but it's hardly a human rights crime*. If a crazed librarian decided to stock my kids' school library with hard core porn and copies of Soldier of Fortune magazine, I might raise a teeny objection. Not every book is suitable for children, in fact, and it isn't surprising that not everyone agrees where the line is. My own mother once complained to my school about the book A Taste of Blackberries, in which a character is stung to death by bees, because I cried for a week after reading it (and still can't see the book today without feeling a bit queasy). I'm glad my poor mom never showed up on those lists.

The real problem, of course, is parents trying to impose their religious values onto public school systems. Such impositions should not be allowed to happen, and fortunately they rarely are. But the Banned Books discussion is not framed that way; instead, the misguided attempts to remove books with too much (or the wrong kind of) sex or witchcraft or swearing are described as violations of intellectual freedom. Perhaps they shouldn't be given so much credit.

The Cities of Refuge project (formerly Cities of Asylum) gives refuge to writers who really have been banned -- Ithaca is currently hosting Sarah Mkhonza, who was threatened and assaulted in her native Swaziland for criticizing the government in her newspaper columns. Iranian writer Reza Daneshvar, here from 2003 to 2006, was jailed for writing a novel about the 1953 coup. Other exiled writers are staying in Las Vegas, Pittsburgh, and Santa Fe. It would be a great thing if other cities followed suit and brought even more writers here to have some time and space to write freely.

*Anyway, there's an easy solution to the cartoon penis, as the librarian at my elementary school discovered: she cut out a tiny pair of paper undies and taped them onto the naked child in the school's copy of In the Night Kitchen.

Thursday, October 18, 2007

Book Binge

Well, it's pretty hard to turn off the internal critic, as you'd think I'd have figured out by now. I couldn't find a copy of The Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England, my store's clean out of them, so I borrowed Alice Sebold's The Almost Moon instead. I don't know what I expected -- I didn't read her first book, since I avoid murdered-kid novels -- but sentences like This was not the first time I'd come face-to-face with my mother's genitalia was not it.

One is reluctant to pile on after Lee Siegel's devastating review in the New York Times Book Review, in which he implied that Sebold's readers are insane. Interestingly, he also got a key plot point wrong, as Galleycat points out. (Siegel makes a big deal out of the murdered mom being put into the freezer, and there's even a cartoon of the mom in a freezer in the NYBTR, but in the book the mom is never actually put there.) The obvious conclusion to jump to is that Siegel didn't really read the book; however, I'll vouch for the fact that, having read it (albeit speedily), it's an easy mistake to make. (Hm... Lee Siegel is the guy who got in trouble at the New Republic for online sock-puppeting: making up an alias and using it to defend his own work. Nervy!)

In any event, I can't say The Almost Moon assisted me in my quest to just have fun reading. It's not fun.

However, I did enjoy Jim Shepard's Like You'd Understand Anyway, at least somewhat. It's very much a guy book: lots of research (Russian nuclear reactors, the Roman Empire, etc.,) not a lot of girly mooning around, not a lot of girls, actually. He's smart and talented and obviously carrying out a very clear vision, and for this I respect him.

Also I got started on Stephen Dixon's Meyer. Just a few pages in but I love it -- love being in Dixon's mind. The novel's about a writer with writer's block, so I'm relating.

One is reluctant to pile on after Lee Siegel's devastating review in the New York Times Book Review, in which he implied that Sebold's readers are insane. Interestingly, he also got a key plot point wrong, as Galleycat points out. (Siegel makes a big deal out of the murdered mom being put into the freezer, and there's even a cartoon of the mom in a freezer in the NYBTR, but in the book the mom is never actually put there.) The obvious conclusion to jump to is that Siegel didn't really read the book; however, I'll vouch for the fact that, having read it (albeit speedily), it's an easy mistake to make. (Hm... Lee Siegel is the guy who got in trouble at the New Republic for online sock-puppeting: making up an alias and using it to defend his own work. Nervy!)

In any event, I can't say The Almost Moon assisted me in my quest to just have fun reading. It's not fun.

However, I did enjoy Jim Shepard's Like You'd Understand Anyway, at least somewhat. It's very much a guy book: lots of research (Russian nuclear reactors, the Roman Empire, etc.,) not a lot of girly mooning around, not a lot of girls, actually. He's smart and talented and obviously carrying out a very clear vision, and for this I respect him.

Also I got started on Stephen Dixon's Meyer. Just a few pages in but I love it -- love being in Dixon's mind. The novel's about a writer with writer's block, so I'm relating.

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

Junot Díaz' The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Like a lot of people, I've been waiting for this book for a hell of a long time. There was a period a decade or so ago when Junot seemed to be publishing a new story every couple of months, and then his book came out, and it was so full of crazy energy that you figured he would be one of those guys who would just crank out stuff like a madman for the rest of his life, and it would all be awesome.

That's not how it worked out, though--he told me once a long while back that he had written a science fiction novel, of all things, and then that didn't pan out, and nothing of his appeared anywhere for a while. Then the "Oscar Wao" novella--which is a part of this new book--came out in the New Yorker, and it was instantly my favorite thing he'd ever written. He'd told people that it was modeled on "Heart of Darkness," and it ended with a mirror image of Kurtz's final words: "The beauty! The beauty!"

I didn't know what I expected with this thing. But I would never in a million years have guessed at what I actually got--this wild, ambitious, brutal, and unbelievable dorky masterpiece. The book reaches back through three generations of a Dominican family (the hapless Oscar's), and in doing so delivers a comic and horrifying gloss on twentieth-century Dominican history, with particular attention to the Trujillo regime of the thirties, forties, and fifties. The thesis here seems to be that the DR is somehow cursed, or maybe blessed, or maybe they're kind of the same thing; and the Dominican culture presented here is one of extremes--exile and return, unspeakable love and unspeakable violence, beauty and horror. And Oscar Wao, the protagonist, serves as the repository of all this insanity.

Oscar is a fantastic character, a classic. He's the first literary character I have ever read who represents so skillfully the tragic majesty of the consummate dork--sci-fi, D&D, Tolkein, the whole nine yards. Oscar is fat, horny, awkward, and pitiful, and his fall is the fall of the dork, though his redemption is the redemption of the hero. He's a stunner.

But what really impresses me here, and what's really strange about this novel, is what Díaz has done with Yunior, his perpetual narrator and alter ego. Yunior isn't Díaz, but boy is the guy asking for comparisons; he is Díaz' Zuckerman, his doppelganger. Yunior has always had a bit of the tragic to him; his masculine bluster serves as the comic fuel of Díaz' early stories, but ultimately Yunior is sad, he can't bring himself to say what needs to be said, he won't connect the dots for his listener. (And I mean listener, not reader, because the voice of Díaz' work is the sound of Yunior talking.) In this book, Yunior can't bring himself even to put the words "I love you" into his characters' mouths; they appear as three blanks, ____ ____ ____, like the names of towns in old Russian novels.

Something has changed with Yunior, though. He's onto himself, and Díaz provides, for the first time, a real sense of what he's become--a resigned ex-lothario teaching at a community college in Perth Amboy. More importantly, the dork in Yunior has emerged, and the novel is laced with the language of comics, monster movies, fantasy and horror novels, and role-playing games. Seriously, you can't turn a page here without hearing somebody compared to an orc. Yunior reveals himself slowly--he only appears as a character halfway through, and before that speaks most directly in footnotes. The result is shockingly meta, for a writer whose stock in trade had always been directness, but in retrospect you can see it brewing, this complex relationship to the self, both in the way Yunior talked about other people and the way Díaz talked about Yunior.

The spectacle of Yunior coming clean--about the workings of his mind, about his philandering and its consequences, about his disloyalty to friends and lovers--is really something to behold. It's amazingly intimate and candid, and as a result the avalanche of obscure pop culture references and untranslated Spanish seem, for the uninitiated, somehow inclusive rather than alienating. You're hearing this narrator's total, unvarnished self for the first time in this writer's career.

Even Díaz' presumably-abandoned SF novel seems to be making an appearance, as a lost manuscript of Oscar's--at least I like to think that's what those missing pages are. The book is full of little oddities like this, things that might be secrets, or magic spells, or maybe just trinkets. The book is all over the place, but nevertheless highly focused. I can't explain. It's manic and wildly successful, and just totally, unabashedly weird. As Yunior says, at one point: cue the theremins.

That's not how it worked out, though--he told me once a long while back that he had written a science fiction novel, of all things, and then that didn't pan out, and nothing of his appeared anywhere for a while. Then the "Oscar Wao" novella--which is a part of this new book--came out in the New Yorker, and it was instantly my favorite thing he'd ever written. He'd told people that it was modeled on "Heart of Darkness," and it ended with a mirror image of Kurtz's final words: "The beauty! The beauty!"

I didn't know what I expected with this thing. But I would never in a million years have guessed at what I actually got--this wild, ambitious, brutal, and unbelievable dorky masterpiece. The book reaches back through three generations of a Dominican family (the hapless Oscar's), and in doing so delivers a comic and horrifying gloss on twentieth-century Dominican history, with particular attention to the Trujillo regime of the thirties, forties, and fifties. The thesis here seems to be that the DR is somehow cursed, or maybe blessed, or maybe they're kind of the same thing; and the Dominican culture presented here is one of extremes--exile and return, unspeakable love and unspeakable violence, beauty and horror. And Oscar Wao, the protagonist, serves as the repository of all this insanity.

Oscar is a fantastic character, a classic. He's the first literary character I have ever read who represents so skillfully the tragic majesty of the consummate dork--sci-fi, D&D, Tolkein, the whole nine yards. Oscar is fat, horny, awkward, and pitiful, and his fall is the fall of the dork, though his redemption is the redemption of the hero. He's a stunner.

But what really impresses me here, and what's really strange about this novel, is what Díaz has done with Yunior, his perpetual narrator and alter ego. Yunior isn't Díaz, but boy is the guy asking for comparisons; he is Díaz' Zuckerman, his doppelganger. Yunior has always had a bit of the tragic to him; his masculine bluster serves as the comic fuel of Díaz' early stories, but ultimately Yunior is sad, he can't bring himself to say what needs to be said, he won't connect the dots for his listener. (And I mean listener, not reader, because the voice of Díaz' work is the sound of Yunior talking.) In this book, Yunior can't bring himself even to put the words "I love you" into his characters' mouths; they appear as three blanks, ____ ____ ____, like the names of towns in old Russian novels.

Something has changed with Yunior, though. He's onto himself, and Díaz provides, for the first time, a real sense of what he's become--a resigned ex-lothario teaching at a community college in Perth Amboy. More importantly, the dork in Yunior has emerged, and the novel is laced with the language of comics, monster movies, fantasy and horror novels, and role-playing games. Seriously, you can't turn a page here without hearing somebody compared to an orc. Yunior reveals himself slowly--he only appears as a character halfway through, and before that speaks most directly in footnotes. The result is shockingly meta, for a writer whose stock in trade had always been directness, but in retrospect you can see it brewing, this complex relationship to the self, both in the way Yunior talked about other people and the way Díaz talked about Yunior.

The spectacle of Yunior coming clean--about the workings of his mind, about his philandering and its consequences, about his disloyalty to friends and lovers--is really something to behold. It's amazingly intimate and candid, and as a result the avalanche of obscure pop culture references and untranslated Spanish seem, for the uninitiated, somehow inclusive rather than alienating. You're hearing this narrator's total, unvarnished self for the first time in this writer's career.

Even Díaz' presumably-abandoned SF novel seems to be making an appearance, as a lost manuscript of Oscar's--at least I like to think that's what those missing pages are. The book is full of little oddities like this, things that might be secrets, or magic spells, or maybe just trinkets. The book is all over the place, but nevertheless highly focused. I can't explain. It's manic and wildly successful, and just totally, unabashedly weird. As Yunior says, at one point: cue the theremins.

Monday, October 15, 2007

Weird Stories

There's a class where I teach, English 785, Reading For Writers; it's a kind of amorphous craft seminar for MFA and PhD students. I'm on the roster for it next semester, and the course packets are due in a few weeks, and I'm trying to compile my materials--the title of my section will be called Weird Stories.

Though I've never considered myself a devotee of "experimental" fiction, I do like literary fiction that strays outside the bounds of representational reality. I don't just mean plot excursions, but adventures in narrative structure, voice, and the logical underpinnings of the story--all the building blocks of fiction which we take for granted,.

There are some obvious places to start--I'll likely throw in a bit of Poe and Irving; some Garcia Marquez, Babel, Nabokov. But I'd like to find stuff that doesn't get taught very often. I'm definitely going to include China Miéville's "Reports of Certain Events in London," a story-in-fragments about the migratory streets of London--it's reminiscient of Arthur C. Clarke's Tales From The White Hart, my favorite book as a kid (and perhaps I should throw in one of those stories, too). In the same vein, I should probably include some Ray Bradbury or Stanislaw Lem, and (lord help me) Stephen King.

Lydia Davis will have to make an appearance, as an innovator in narrative structure, along with David Foster Wallace; we'll also certainly read Stephen Dixon's hilarious "Love Has Its Own Action," which works like no other story I've read, and maybe his "14 Stories," as well. John Barth, of course, though I appreciate more than love his work.

I like ghost stories and supernatural tales (Rhian doesn't, I don't think), so I might be forced to include some Joyce Carol Oates, though perhaps the grad students have had enough of her (or perhaps they've never read her, most of them having been too young in the eighties, her heyday). Alice Munro's "Carried Away" will be included--it's kind of a ghost story, but more of just a story where something impossible happens, without comment. There's an A. S. Byatt story, "The July Ghost," that I remember liking, but I wonder if I'd like it today.

Kelly Link will be included, too--I don't even know where to begin to categorize her work.

Anyway, the pile of books is growing and I am feeling exhausted just looking at it. Any suggestions?

Though I've never considered myself a devotee of "experimental" fiction, I do like literary fiction that strays outside the bounds of representational reality. I don't just mean plot excursions, but adventures in narrative structure, voice, and the logical underpinnings of the story--all the building blocks of fiction which we take for granted,.

There are some obvious places to start--I'll likely throw in a bit of Poe and Irving; some Garcia Marquez, Babel, Nabokov. But I'd like to find stuff that doesn't get taught very often. I'm definitely going to include China Miéville's "Reports of Certain Events in London," a story-in-fragments about the migratory streets of London--it's reminiscient of Arthur C. Clarke's Tales From The White Hart, my favorite book as a kid (and perhaps I should throw in one of those stories, too). In the same vein, I should probably include some Ray Bradbury or Stanislaw Lem, and (lord help me) Stephen King.

Lydia Davis will have to make an appearance, as an innovator in narrative structure, along with David Foster Wallace; we'll also certainly read Stephen Dixon's hilarious "Love Has Its Own Action," which works like no other story I've read, and maybe his "14 Stories," as well. John Barth, of course, though I appreciate more than love his work.

I like ghost stories and supernatural tales (Rhian doesn't, I don't think), so I might be forced to include some Joyce Carol Oates, though perhaps the grad students have had enough of her (or perhaps they've never read her, most of them having been too young in the eighties, her heyday). Alice Munro's "Carried Away" will be included--it's kind of a ghost story, but more of just a story where something impossible happens, without comment. There's an A. S. Byatt story, "The July Ghost," that I remember liking, but I wonder if I'd like it today.

Kelly Link will be included, too--I don't even know where to begin to categorize her work.

Anyway, the pile of books is growing and I am feeling exhausted just looking at it. Any suggestions?

Sunday, October 14, 2007

That New Book Smell

I do a weird thing when I'm shelving new books at the bookstore: I crack them open and take a whiff. Every book smells subtly different; each has a different combination of chemically-gluey-inky-woody-plasticky-cardboard-boxy. Those smells are like time machines. Once in a while I smell a book that's exactly like an elementary school textbook, and for a moment I can see my old classrooms, and I remember how exciting a new textbook was and how its uncracked spine and glossy pages promised so much. Mass-market paperbacks have a particular bitter smell that goes with their rough pages; it makes me think of lying on the living room carpet when I was a teenager, reading The Amityville Horror. When I was a kid I didn't pay much attention to the smell of books or the feel of their spines or the quality of their paper, but I must have absorbed it all while reading. Now whenever I hold a book or smell a book I'm flooded with little half-memories of reading pleasure.

Both our sons like to read -- the older one reads pretty much anything but the younger one is a comic book aficionado. It's impossible to walk across his room with slipping on mounds of comics, everywhere. The other day when he finished his homework he said, "Hurray! Now I can go read my comic book!" and boy, did I envy him, to be able to get so much endlessly renewable pleasure out of reading. Because it's not like that for me so much anymore -- I'm too picky, too judgey, too easily disappointed. I wonder: is it possible to get it back, that ability to go from one book to the next indiscriminately, just pulling whatever enjoyment I can from every book?

I'm going to try, I think. For the next couple of weeks, anyway, until NaNoWriMo, I'm going to read as many novels as possible with an eye to just having fun. I'll skip the boring bits and not take any notes or even pause to come up with a cutting criticism. Part of the problem, of course, is that books are expensive, and it's easy to feel disappointed when you pay $27.00 for a novel that isn't great. So I'll have to get them from the library's mixed bag or borrow them from my store (and just be careful not to spill on them).

I think I'll start with An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England.

Both our sons like to read -- the older one reads pretty much anything but the younger one is a comic book aficionado. It's impossible to walk across his room with slipping on mounds of comics, everywhere. The other day when he finished his homework he said, "Hurray! Now I can go read my comic book!" and boy, did I envy him, to be able to get so much endlessly renewable pleasure out of reading. Because it's not like that for me so much anymore -- I'm too picky, too judgey, too easily disappointed. I wonder: is it possible to get it back, that ability to go from one book to the next indiscriminately, just pulling whatever enjoyment I can from every book?

I'm going to try, I think. For the next couple of weeks, anyway, until NaNoWriMo, I'm going to read as many novels as possible with an eye to just having fun. I'll skip the boring bits and not take any notes or even pause to come up with a cutting criticism. Part of the problem, of course, is that books are expensive, and it's easy to feel disappointed when you pay $27.00 for a novel that isn't great. So I'll have to get them from the library's mixed bag or borrow them from my store (and just be careful not to spill on them).

I think I'll start with An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England.

Friday, October 12, 2007

T. C. Boyle, "Sin Dolor"

A professional acquaintance of mine was warning me the other day of the dangers of overexposure. "You know," he said, "it's possible to publish too much." He must know me better than I thought he did, because this is a problem of mine--I want to be in every magazine, every month, forever. I don't want a single human being on earth to forget about me for one moment. Needless to say, this is not healthy, not for my psyche and definitely not for my career.

But for some reason it hasn't seemed to put a dent in T. C. Boyle's. Like Joyce Carol Oates in the eighties, he is everywhere, and his period of everywhereness seems to have extended longer than Oates's. He is absolutely a fixture--a writing addict.

Honestly, I don't mind. You can expect a certain quality of product from Boyle. I'm sure a hundred reviewers have called him a "master," and bully for him, but he's not. He is stunningly competent, though, and his stories are always enjoyable.

This one, from this week's otherwise-anemic New Yorker, is no exception. It's about a small-town Mexican doctor, a bit of a snob, who delivers a child incapable of feeling pain. He watches the boy grow, and grow more morose and desperate, as his father transforms him into a sideshow act. Terribly aged (though painlessly) at thirteen, the boy finally dies when he is challenged by some kids to jump off a building.

I like the narration of this story--it is free of the big overspiced mouthfuls of prose Boyle is sometimes prone to, and fizzes with a surprising and very appealing arrogance. The doctor's a bit of a prick, and is proud of it. But the problem with a Boyle story--and this one is no exception--is that you can see where it's going from a mile off. It's a beautiful, symmetrical construction, fitting as nicely into the literary landscape as a classic brownstone into a Manhattan street. This particular story comes off as a kind of Kafka lite, like "The Hunger Artist" except you'll never have an argument with anybody about it, like Marquez but somehow not as grand. The plot is smooth, the pieces fall gently together, and the dialogue sounds like it was taken from the movie that will someday be made of it. It's solid, and kind of disappointing.

This kind of flaw really stings me, because it's exactly the kind of thing I'm prone to--moral and emotional tidiness. So I'm likely to find greater fault with it than most people would. I sometimes feel like Boyle's shadow: the skinny bespectacled dude with an initial initial who writes too much, except I have a less adventurous hairdo and will always be less famous.

That said, Boyle is never going to flame out, and this is an enviable position to be in. I feel like his work is more inspiring to writers than it is to general readers--he makes you feel like writing is something you can do. He has always made me feel that way, anyhow, and that's worth being grateful for.

But for some reason it hasn't seemed to put a dent in T. C. Boyle's. Like Joyce Carol Oates in the eighties, he is everywhere, and his period of everywhereness seems to have extended longer than Oates's. He is absolutely a fixture--a writing addict.

Honestly, I don't mind. You can expect a certain quality of product from Boyle. I'm sure a hundred reviewers have called him a "master," and bully for him, but he's not. He is stunningly competent, though, and his stories are always enjoyable.

This one, from this week's otherwise-anemic New Yorker, is no exception. It's about a small-town Mexican doctor, a bit of a snob, who delivers a child incapable of feeling pain. He watches the boy grow, and grow more morose and desperate, as his father transforms him into a sideshow act. Terribly aged (though painlessly) at thirteen, the boy finally dies when he is challenged by some kids to jump off a building.

I like the narration of this story--it is free of the big overspiced mouthfuls of prose Boyle is sometimes prone to, and fizzes with a surprising and very appealing arrogance. The doctor's a bit of a prick, and is proud of it. But the problem with a Boyle story--and this one is no exception--is that you can see where it's going from a mile off. It's a beautiful, symmetrical construction, fitting as nicely into the literary landscape as a classic brownstone into a Manhattan street. This particular story comes off as a kind of Kafka lite, like "The Hunger Artist" except you'll never have an argument with anybody about it, like Marquez but somehow not as grand. The plot is smooth, the pieces fall gently together, and the dialogue sounds like it was taken from the movie that will someday be made of it. It's solid, and kind of disappointing.

This kind of flaw really stings me, because it's exactly the kind of thing I'm prone to--moral and emotional tidiness. So I'm likely to find greater fault with it than most people would. I sometimes feel like Boyle's shadow: the skinny bespectacled dude with an initial initial who writes too much, except I have a less adventurous hairdo and will always be less famous.

That said, Boyle is never going to flame out, and this is an enviable position to be in. I feel like his work is more inspiring to writers than it is to general readers--he makes you feel like writing is something you can do. He has always made me feel that way, anyhow, and that's worth being grateful for.

Thursday, October 11, 2007

Hungry

Except for a few short stories, I haven't read any fiction since Exit Ghost. I just haven't felt like it. But about an hour ago I had a sudden craving -- I wanted to read a novel. Not just any novel, though. Like a food craving, this craving was for something specific: something quick, rich, funny, and maybe historical. (Weird, I hardly ever read historical fiction.) I caught a glimpse of it: some people laughing, rain on a window... Sigmund Freud. Yes! I want to read a novel about Sigmund Freud!

Where does such a craving come from? Maybe the sudden change in weather -- after days of bizarre heat and humidity, today it's chilly and raining -- makes me want to recreate the experience of first reading The World As I Found It, a quickly moving (though deliciously long), rich, funny, historical novel. And I've been thinking about Lauren Slater's Opening Skinner's Box, a collection of essays about psychological experiments. It sounds so tasty: a novel like TWAIFI but about psychology. Has anyone written it??

I wonder how many people have written novels just because they had a particular craving to read something that didn't yet exist?

Where does such a craving come from? Maybe the sudden change in weather -- after days of bizarre heat and humidity, today it's chilly and raining -- makes me want to recreate the experience of first reading The World As I Found It, a quickly moving (though deliciously long), rich, funny, historical novel. And I've been thinking about Lauren Slater's Opening Skinner's Box, a collection of essays about psychological experiments. It sounds so tasty: a novel like TWAIFI but about psychology. Has anyone written it??

I wonder how many people have written novels just because they had a particular craving to read something that didn't yet exist?

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

Autographs

Condalmo is posting today about Radiohead, and though that's not what this post is about, I wish to say that I downloaded (legally!) the new record today, and it's freakin' fantastic. Very intimate and low-key, with a lot of swampy reverb and crazy stereo imaging, and fuzzed-out bass, and string quartets, and super-dry, popcornesque drumming. And yes, the Radiohead model of selling the record (no label, right off of their website, for however much money you feel like paying) is terrific, and I'd love to do it, but you can only get away with it, at least right now, if you're the best band in the world. And I am not the best band in the world, let alone the best novelist.

But it's this post on Margaret Atwood I want to address. Condalmo doesn't like the Long Pen, comparing it to a photocopier. He writes:

Like Rhian (see the comments of that thread), I disagree with him here--it's autographs themselves that are something of a scam, not the Long Pen. I'm not a terribly popular writer, and I'm always delighted when somebody actually is interested enough in my stuff to want me to sign it. But I have to say, even then, I don't really like doing it.

Most people ask a writer for an autograph because they liked the reading or book, and want to commemorate their having talked with the author. I've asked for lots of autographs this way, and people generally seem happy to to provide them and say hello.

But every medium-sized city on up has at least one Weird Dude (always a dude) who has like multiple copies of your book, with acrylic wrappers on the dust jackets, and wants you to sign them all. "Just your name," they say, with a tiny bit of desperation. As if, should you write, "To Weird Dude, good luck with your search for a girlfriend! Best wishes, J. Robert Lennon," you would ruin everything.

And you would, because they are not trying to commemorate a pleasant human interaction. They don't give a crap about your book. They barely look at you, in fact! No, they're squirreling away your stuff in the unlikely event you become super famous, and then they'll get to make a huge profit selling the signed editions on eBay.

The Weird Dude really brings to light the whole problem with autographs...the fact that a story is ephemeral, and takes a different shape in every reader's mind, and that this is the entire point. That a story is a seed for the individual imagination. That the physical book is not the important thing--let alone one's contact with the author.

Now, I don't mean to demean every autograph seeker, here--most people just like the book and think it's fun to meet the author. I'm one of those people. But I don't really ask for autographs anymore (the last one I asked for, and probably the last I will ever ask for, was Alice Munro's, beside the buffet table in the green room at the Toronto International Book Festival, because hell!, Alice Munro!!), because they seem a little bit gross to me now. The story should be enough. The story is enough. In fact, it's more than I have any right to ask for, and yet I get to have it anyway.

It isn't that Condalmo's wrong, per se, but he is missing the point that author autographs overall are just kind of pointless. And if you're as famous as Margaret Atwood, you could spend your whole damned life sitting at a pressboard buffet table gazing up in exhaustion at the Weird Dude, and why not make something that can obliterate that experience from your life?

But it's this post on Margaret Atwood I want to address. Condalmo doesn't like the Long Pen, comparing it to a photocopier. He writes:

I would never in a hundred years line up for a photocopy of a signature from any author. For an author to agree to participation in such a "author appearance" or "book signing" ("event", "reading", "respectful interaction with readers") makes me much less likely to feel any interest in that author's writing.

Like Rhian (see the comments of that thread), I disagree with him here--it's autographs themselves that are something of a scam, not the Long Pen. I'm not a terribly popular writer, and I'm always delighted when somebody actually is interested enough in my stuff to want me to sign it. But I have to say, even then, I don't really like doing it.

Most people ask a writer for an autograph because they liked the reading or book, and want to commemorate their having talked with the author. I've asked for lots of autographs this way, and people generally seem happy to to provide them and say hello.

But every medium-sized city on up has at least one Weird Dude (always a dude) who has like multiple copies of your book, with acrylic wrappers on the dust jackets, and wants you to sign them all. "Just your name," they say, with a tiny bit of desperation. As if, should you write, "To Weird Dude, good luck with your search for a girlfriend! Best wishes, J. Robert Lennon," you would ruin everything.

And you would, because they are not trying to commemorate a pleasant human interaction. They don't give a crap about your book. They barely look at you, in fact! No, they're squirreling away your stuff in the unlikely event you become super famous, and then they'll get to make a huge profit selling the signed editions on eBay.

The Weird Dude really brings to light the whole problem with autographs...the fact that a story is ephemeral, and takes a different shape in every reader's mind, and that this is the entire point. That a story is a seed for the individual imagination. That the physical book is not the important thing--let alone one's contact with the author.

Now, I don't mean to demean every autograph seeker, here--most people just like the book and think it's fun to meet the author. I'm one of those people. But I don't really ask for autographs anymore (the last one I asked for, and probably the last I will ever ask for, was Alice Munro's, beside the buffet table in the green room at the Toronto International Book Festival, because hell!, Alice Munro!!), because they seem a little bit gross to me now. The story should be enough. The story is enough. In fact, it's more than I have any right to ask for, and yet I get to have it anyway.

It isn't that Condalmo's wrong, per se, but he is missing the point that author autographs overall are just kind of pointless. And if you're as famous as Margaret Atwood, you could spend your whole damned life sitting at a pressboard buffet table gazing up in exhaustion at the Weird Dude, and why not make something that can obliterate that experience from your life?

Tuesday, October 9, 2007

It's Almost Novelember

I've done National Novel Writing Month -- an online challenge for participants to write an entire 200 page novel during the month of November -- for the last couple of years, and I plan on doing it again this year. I really love it. I love knocking out those pages and typing my daily wordcount into the website's graphing thing, etc. (Take a look at the website: it's really neato).

However, I'm not sure how useful it is to a person, such as myself, who takes writing perhaps a little too seriously and wants to do it well. In order to produce that many pages in a month, most of us have to wrestle our internal critic aside and just write anything. That can be a great relief and lots of fun for a person, such as myself, who has a bully for an internal critic, but how useful is it? Can it produce work worth reading? I'm not so sure. My first NaNoWriMo novel was pretty unintelligible; maybe one paragraph out of the 200 pages was something I'd want to keep (it described a character's losing an eye, haha). The second one had more decent stuff in it, but it, too, was as close to being a real novel as my latest grocery list.

It makes me question the whole idea of the "shitty first draft," the creative writing idea (Anne Lamott's, I think) that just getting words down on paper, any old words, is better than nothing, because then, at least, you have something to revise. But the work involved in polishing this "shit" is often much more overwhelming than writing a thoughtful draft in the first place.

Ugh -- but then again. It's true that you can come up with marvelous, inspired stuff if you're just counting pages and aren't too fixated on its being marvelous and inspired. And is it not true that my last NaNoNovel is the only thing I've come even close to finishing in a very long time?

Anyway, whether or not NaNoWriMo produces anything worthwhile is beside the point. Isn't it? If one takes writing too seriously, it's probably not for one.

However, I'm not sure how useful it is to a person, such as myself, who takes writing perhaps a little too seriously and wants to do it well. In order to produce that many pages in a month, most of us have to wrestle our internal critic aside and just write anything. That can be a great relief and lots of fun for a person, such as myself, who has a bully for an internal critic, but how useful is it? Can it produce work worth reading? I'm not so sure. My first NaNoWriMo novel was pretty unintelligible; maybe one paragraph out of the 200 pages was something I'd want to keep (it described a character's losing an eye, haha). The second one had more decent stuff in it, but it, too, was as close to being a real novel as my latest grocery list.

It makes me question the whole idea of the "shitty first draft," the creative writing idea (Anne Lamott's, I think) that just getting words down on paper, any old words, is better than nothing, because then, at least, you have something to revise. But the work involved in polishing this "shit" is often much more overwhelming than writing a thoughtful draft in the first place.

Ugh -- but then again. It's true that you can come up with marvelous, inspired stuff if you're just counting pages and aren't too fixated on its being marvelous and inspired. And is it not true that my last NaNoNovel is the only thing I've come even close to finishing in a very long time?

Anyway, whether or not NaNoWriMo produces anything worthwhile is beside the point. Isn't it? If one takes writing too seriously, it's probably not for one.

Monday, October 8, 2007

Sibling Books

Posting has been light lately, because of houseguests--Rhian's sister and our neices came to stay for a couple of days. R. and her sis get on pretty well, as do I with my brother--but siblings are a fine subject for a book. I wrote a couple of sibling novels in a row, one funny, one grim; here are a few good ones I can think of.

Chris Offutt, The Good Brother. The first, and so far only, novel by this W6 chum (well--we haven't seen him in years, but still) is about a man from a Kentucky mountain clan who flees his community when he is expected to murder, in revenge for a previous killing, a member of another clan. He flees to Montana where, wouldn't you know it!, ends up entangled with a heavily armed separatist cult. Gripping and odd.

Maria Flook, My Sister Life. I'm ordinarily no fan of memoirs, but I really liked this strange story. Flook's sister disappeared at 14, and the two went on to live lives of depressing similarity; they later reunite in harrowing circumstances. Looking at that link, I see that Flook's got a story collection too--I didn't know that. Will have to give it a look.

I wasn't crazy about Donald Antrim's first book, when it came out, but there was something about it that I couldn't shake, and I've become a fan, especially ever since his memoir last year. (See, there I go again, liking a memoir.) My fandom began, though, with The Hundred Brothers, a novel that's about precisely what it sounds like it's about, and never ceases to be inventive and funny.

I think maybe the best sister novel ever is by the endlessly flabbergasting Kathryn Davis (my favorite of hers is The Walking Tour, but it doesn't fit the post)--her first novel, Labrador. It's a work of stunning imagination and sophistication; suffice it to say it's not about sisters getting together, drinking chamomile tea, discussing boyfriends, and crying on one another's shoulders.

Finally, I have to throw in a mention of the many sibling writers--the Brontes, the Jameses; A. S. Byatt and Margaret Drabble; and now we've got the Bender sisters, the Sedarises (Amy's entertaining book is funny enough to make you vomit), and aren't there a bunch of Minots?

Chris Offutt, The Good Brother. The first, and so far only, novel by this W6 chum (well--we haven't seen him in years, but still) is about a man from a Kentucky mountain clan who flees his community when he is expected to murder, in revenge for a previous killing, a member of another clan. He flees to Montana where, wouldn't you know it!, ends up entangled with a heavily armed separatist cult. Gripping and odd.

Maria Flook, My Sister Life. I'm ordinarily no fan of memoirs, but I really liked this strange story. Flook's sister disappeared at 14, and the two went on to live lives of depressing similarity; they later reunite in harrowing circumstances. Looking at that link, I see that Flook's got a story collection too--I didn't know that. Will have to give it a look.

I wasn't crazy about Donald Antrim's first book, when it came out, but there was something about it that I couldn't shake, and I've become a fan, especially ever since his memoir last year. (See, there I go again, liking a memoir.) My fandom began, though, with The Hundred Brothers, a novel that's about precisely what it sounds like it's about, and never ceases to be inventive and funny.

I think maybe the best sister novel ever is by the endlessly flabbergasting Kathryn Davis (my favorite of hers is The Walking Tour, but it doesn't fit the post)--her first novel, Labrador. It's a work of stunning imagination and sophistication; suffice it to say it's not about sisters getting together, drinking chamomile tea, discussing boyfriends, and crying on one another's shoulders.

Finally, I have to throw in a mention of the many sibling writers--the Brontes, the Jameses; A. S. Byatt and Margaret Drabble; and now we've got the Bender sisters, the Sedarises (Amy's entertaining book is funny enough to make you vomit), and aren't there a bunch of Minots?

Friday, October 5, 2007

Best American Essays 2007

Damn--this is a very fine anthology. I had stopped buying these, but this year has not only got me excited about the series, it's got me excited about the essay. I am actually thinking of writing a few.

Most of the credit can go to David Foster Wallce, this year's guest editor, whose terrific introduction tells me that most of the credit should not go to David Foster Wallace, actually, but to series editor Robert Atwan, whom Wallace envisions

I love Wallace's stuff, and loved it even through the years when he was most hyped (as a result of Infinite Jest, ironically the one thing of his I never much got into), and I happen to think the essay is where he's at his most excellent. He says that just because you think somebody is a good writer, doesn't mean he's a good reader--but it turns out Wallace is, because these essays are great.