W6 readers, give me a hand with something, will you? I'm designing a new Cornell class, a First-Year Seminar called Crime Stories. It will be a survey of crime fiction since the dawn of time, with written critical responses. (I always allow at least one creative one, too.)

I have a few things I will definitely use: The Big Sleep. Sjowall and Wahloo's The Laughing Policeman. One heist novel, probably one of Richard Stark's Parker novels. One genre-buster, perhaps Jonathan Lethem's Gun, With Occasional Music or China Mieville's recent The City And The City. I will of course use a Poe story and a Conan Doyle story.

But what else? I'd like more women (besides Maj Sjowall). Dorothy Sayers? Patricia Highsmith? (Maybe Strangers On A Train.) I wouldn't mind using Tana French's The Likeness, but it's rather long. Ruth Rendell / Barbara Vine? She writes great crime novels but I don't know what I'd say about them in a college class. Karin Fossum perhaps? Can a case be made for Shirley Jackson? I am thinking of We Have Always Lived In The Castle.

Or writers of color--Walter Mosley? I'd like to get a couple more pre-war writers maybe. It's a 14-week semester and each week will be either one or two short stories, or a short novel, or half a long novel. Would love your ideas. Especially if you are a Cornell freshman who happens to be registered for the class.

Showing posts with label crime. Show all posts

Showing posts with label crime. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Saturday, March 14, 2009

Thrillers and class

Can we talk for a moment about the world of mysteries and thrillers and its bizarre obsession with class? This week I went to the library and took out my usual stack of crime fiction, hoping one or two of the half dozen would work out all right, and this blurb caught my eye. It's on the back of the Peter Abrahams novel Deception, and is taken from a review by Michele Ross, published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, of Abrahams' last book, Nerve Damage:

Where do I start? Good god. I suppose the obvious place is to ask who on earth these "literary people" are who hesitate, repulsed, before uttering the word "mysteries." As a literary person who spends almost all of my time with literary people, I have never met one. Indeed, some of the best recommendations for mysteries that I get come from the English department at Cornell, where I enjoy the benefit of an informal mystery-trading ring with, among others, a wunderkind Shakespeare scholar, one of the world's premier poststructuralists, and a department secretary. In other words, just about everyone enjoys mysteries, and there's really nobody who needs to be smacked on the head.

Of course I'm not going to blame Abrahams for his reviewer's comments. This is my third try at Abrahams, and I made it farther than ever before. But now I give up. He's not bad, but the book is so packed with "good writing" that I can't see the plot for all the fog; "good writing" in this case refers to the florid metaphoric overdescription of mundane detail that writers fill their books with when they're out of their depth. Meanwhile, the protagonist of Delusion is a sexy airhead who can't put two and two together. A pass, for me.

Next on the pile is The Silver Bear, the debut novel, about a contract killer, from screenwriter Derek Haas. It's appealingly slim and gives good flap, but the ponderous first-person narrative lost me within sentences. This is from the first paragraph:

Uh huh. Of all the things this narrator can open his story with, he feels the need to tell us, right up front, that he IS NOT MIDDLE CLASS, OKAY?!? What professional murderer would care to ever say any such thing? This isn't the character speaking, here, it's the writer speaking to the audience, assuring them that they will be soon enjoy the frisson of empathizing with somebody outside their immediate value system. This reminds me of why I rarely like any first-person killer novels; I just never believe that this person would be talking at all. Even my favorite thrillerist, Lee Child, occasionally indulges in first-person narratives from his hero, Jack Reacher; these are terrific books, but when you read them, you have to block from your mind the absolute knowledge that Reacher would never in a million years say so many words at once.

Okay, scratch Derek Haas. Bring on the new Stephen King, Just After Sunset, which, let me say from the start, is in places really good. A few stories in here--"N.", "Harvey's Dream", "The New York Times At Special Bargain Rates"--are some of the best things King has written, so hooray for that. "Harvey's Dream" is particularly creepy.

But as regular readers of this blog already know, I consider King to be the king of class paranoia, and he doesn't disappoint. Here we have Henry, the soon-to-be-divorced husband of the protagonist of "The Gingerbread Girl," reacting to the news that she'll soon be visiting his working-class father's beach house:

This is classic King--in a world of ghosts, monsters, and murderers, pretension is the ultimate enemy. Of course, Stephen King is very smart, and loves all kinds of literature, and can't resist referring, in his books, to all the great writers, musicians, and artists he has enjoyed in his life. And there is nothing wrong with that. But when he puts this knowledge into the minds of his characters, we get passages like this, from "The Things They Left Behind":

Right. One of those guys--it's not like I care. I mean, I don't sit around, like, reading all the time, man. Mostly I repair my car and watch sports, but you know how it is, Mac, the way those Magic Realist quotes stick in your head. To be honest, it really fuckin' bugs me.

This post could go on for pages, as you probably know, if you read mysteries and thrillers. The question, of course, is why? Why is class paranoia the default mode for the thrillerist? You would think that the entire genre was made up of people whose greatest fear is that somewhere out there, some elbow-patched lit prof is thinking he's superior to them. Of course the genre was born in the pulps, which didn't used to get any respect; but of course now they do, they're taught in college classes, and oceans of ink about them have been spilled over the dissertations of the world. King especially is now widely lauded as an inspiration for all manner of literary fiction; he's certainly a powerful force behind my new novel.

Crime and thriller writers need to evolve. It's time for them to assume the habits of self-confidence and literary ambition that people like Stephen King have earned for them, and stop trying to have it both ways.

I swear, if one more literary person says in that oh-so-condescendng tone, 'Oh, I don't read ... mysteries,' I'm going to take a novel by Peter Abrahams and smack him on his smug little head.

Where do I start? Good god. I suppose the obvious place is to ask who on earth these "literary people" are who hesitate, repulsed, before uttering the word "mysteries." As a literary person who spends almost all of my time with literary people, I have never met one. Indeed, some of the best recommendations for mysteries that I get come from the English department at Cornell, where I enjoy the benefit of an informal mystery-trading ring with, among others, a wunderkind Shakespeare scholar, one of the world's premier poststructuralists, and a department secretary. In other words, just about everyone enjoys mysteries, and there's really nobody who needs to be smacked on the head.

Of course I'm not going to blame Abrahams for his reviewer's comments. This is my third try at Abrahams, and I made it farther than ever before. But now I give up. He's not bad, but the book is so packed with "good writing" that I can't see the plot for all the fog; "good writing" in this case refers to the florid metaphoric overdescription of mundane detail that writers fill their books with when they're out of their depth. Meanwhile, the protagonist of Delusion is a sexy airhead who can't put two and two together. A pass, for me.

Next on the pile is The Silver Bear, the debut novel, about a contract killer, from screenwriter Derek Haas. It's appealingly slim and gives good flap, but the ponderous first-person narrative lost me within sentences. This is from the first paragraph:

If you saw me on the street, you might think, "what a nice, clean-cut young man. I'll bet he works in advertising or perhaps a nice accounting firm. I'll bet he's married and is just starting a family. I'll bet his parents raised him well." But you would be wrong. I am old in a thousand ways.

Uh huh. Of all the things this narrator can open his story with, he feels the need to tell us, right up front, that he IS NOT MIDDLE CLASS, OKAY?!? What professional murderer would care to ever say any such thing? This isn't the character speaking, here, it's the writer speaking to the audience, assuring them that they will be soon enjoy the frisson of empathizing with somebody outside their immediate value system. This reminds me of why I rarely like any first-person killer novels; I just never believe that this person would be talking at all. Even my favorite thrillerist, Lee Child, occasionally indulges in first-person narratives from his hero, Jack Reacher; these are terrific books, but when you read them, you have to block from your mind the absolute knowledge that Reacher would never in a million years say so many words at once.

Okay, scratch Derek Haas. Bring on the new Stephen King, Just After Sunset, which, let me say from the start, is in places really good. A few stories in here--"N.", "Harvey's Dream", "The New York Times At Special Bargain Rates"--are some of the best things King has written, so hooray for that. "Harvey's Dream" is particularly creepy.

But as regular readers of this blog already know, I consider King to be the king of class paranoia, and he doesn't disappoint. Here we have Henry, the soon-to-be-divorced husband of the protagonist of "The Gingerbread Girl," reacting to the news that she'll soon be visiting his working-class father's beach house:

"The conch shack." She could almost hear him sniff. Like Ho Hos and Twinkies, houses with only three rooms and no garage were not a part of Henry's belief system.

This is classic King--in a world of ghosts, monsters, and murderers, pretension is the ultimate enemy. Of course, Stephen King is very smart, and loves all kinds of literature, and can't resist referring, in his books, to all the great writers, musicians, and artists he has enjoyed in his life. And there is nothing wrong with that. But when he puts this knowledge into the minds of his characters, we get passages like this, from "The Things They Left Behind":

I even remember something one of those South American novelists said--you know, the ones they call the Magic Realists? Not the guy's name, that's not important, but this quote: [long quote from "the guy"]. Borges? Yes, it might have been Borges. Or it might have been Marquez.

Right. One of those guys--it's not like I care. I mean, I don't sit around, like, reading all the time, man. Mostly I repair my car and watch sports, but you know how it is, Mac, the way those Magic Realist quotes stick in your head. To be honest, it really fuckin' bugs me.

This post could go on for pages, as you probably know, if you read mysteries and thrillers. The question, of course, is why? Why is class paranoia the default mode for the thrillerist? You would think that the entire genre was made up of people whose greatest fear is that somewhere out there, some elbow-patched lit prof is thinking he's superior to them. Of course the genre was born in the pulps, which didn't used to get any respect; but of course now they do, they're taught in college classes, and oceans of ink about them have been spilled over the dissertations of the world. King especially is now widely lauded as an inspiration for all manner of literary fiction; he's certainly a powerful force behind my new novel.

Crime and thriller writers need to evolve. It's time for them to assume the habits of self-confidence and literary ambition that people like Stephen King have earned for them, and stop trying to have it both ways.

Labels:

crime,

derek haas,

peter abrahams,

Stephen King,

thrillers

Monday, February 16, 2009

Crime: Three for Three?

Those of you who read this blog regularly know that it's my habit to go to the library or bookstore, borrow or buy a big pile of crime novels, then come home and be really disappointed. This time I worked at it, choosing one known element, one with a good hook (photography) and one that just looked weird. And go figure, they're all good.

T. Jefferson Parker, L.A. Outlaws. Parker's pretty much a conventional American crime novelist, but is among the best of that bunch. He doesn't get too arty or ambitious, but he has some interesting ideas, his writing is never awful and is sometimes excellent, and his characters are very memorable. This new book has three great characters--a wildly implausible girl bandit and folk hero who is an elementary school teacher by day; a contemplative, self-possessed cop and Iraq war vet; and a machete-wielding villain. They make a strange triangle: the cop alternately trying to catch the bandit and falling in love with her, the bandit and the cop trying to catch the villain, and the villain trying to kill everyone. The cop will be in Parker's next novel, too, which pleases me. I like the cut of his jib.

Elizabeth Hand, Generation Loss. This is a highly entertaining quasi-literaruy outing that turns into a semi-run-of-the-mill thriller by the end, with a firey conclusion you will roll your eyes at, and a killer who you knew it was all along. But the protagonist is a washed-up punk rock photographer who is sent to interview a washed-up reculsive art photographer, and photography is not merely window dressing here, but a vital and well-researched element that is integral to the plot and characters. Hand makes the usual accoutrements of noir, like alcoholism, drug abuse, and dark thoughts, seem fresh, as well. A blast.

Thomas Glavinic, Night Work. This translation (from German) is not a crime novel, and I'm not sure why The Bookery thought it was. But that's where I found it. The setup: Jonas, a man in his thirties, wakes up one morning and every human being and animal on earth is gone without a trace. I have to admit I'm only halfway through, but so far he's still alone, yet the book is not only fascinating, but one of the scariest fucking things I have ever read. Jonas's solitude drives him to enter a state that is half sleepwalking, half hyperaware, and minute details take on enormous weight. One scene, where he videotapes himself sleeping, then watches the tape to find "The Sleeper" staring at the camera, his eyes wide open, gave me nightmares. A bit reminiscent of my favorite book of last year, Tom McCarthy's Remainder. The writing is austere and serious without sacrificing its sense of ironic humor. If it loses me before the end, I'll let you know.

EDIT: OK, I finished this last night, and I must say, I think this novel is incredible, maybe a masterpiece. And it definitely doesn't belong in the crim section. It's absolutely unflinching, incredibly depressing, and yet I find it strangely life-affirming. Somebody quick translate the rest of his stuff...

T. Jefferson Parker, L.A. Outlaws. Parker's pretty much a conventional American crime novelist, but is among the best of that bunch. He doesn't get too arty or ambitious, but he has some interesting ideas, his writing is never awful and is sometimes excellent, and his characters are very memorable. This new book has three great characters--a wildly implausible girl bandit and folk hero who is an elementary school teacher by day; a contemplative, self-possessed cop and Iraq war vet; and a machete-wielding villain. They make a strange triangle: the cop alternately trying to catch the bandit and falling in love with her, the bandit and the cop trying to catch the villain, and the villain trying to kill everyone. The cop will be in Parker's next novel, too, which pleases me. I like the cut of his jib.

Elizabeth Hand, Generation Loss. This is a highly entertaining quasi-literaruy outing that turns into a semi-run-of-the-mill thriller by the end, with a firey conclusion you will roll your eyes at, and a killer who you knew it was all along. But the protagonist is a washed-up punk rock photographer who is sent to interview a washed-up reculsive art photographer, and photography is not merely window dressing here, but a vital and well-researched element that is integral to the plot and characters. Hand makes the usual accoutrements of noir, like alcoholism, drug abuse, and dark thoughts, seem fresh, as well. A blast.

Thomas Glavinic, Night Work. This translation (from German) is not a crime novel, and I'm not sure why The Bookery thought it was. But that's where I found it. The setup: Jonas, a man in his thirties, wakes up one morning and every human being and animal on earth is gone without a trace. I have to admit I'm only halfway through, but so far he's still alone, yet the book is not only fascinating, but one of the scariest fucking things I have ever read. Jonas's solitude drives him to enter a state that is half sleepwalking, half hyperaware, and minute details take on enormous weight. One scene, where he videotapes himself sleeping, then watches the tape to find "The Sleeper" staring at the camera, his eyes wide open, gave me nightmares. A bit reminiscent of my favorite book of last year, Tom McCarthy's Remainder. The writing is austere and serious without sacrificing its sense of ironic humor. If it loses me before the end, I'll let you know.

EDIT: OK, I finished this last night, and I must say, I think this novel is incredible, maybe a masterpiece. And it definitely doesn't belong in the crim section. It's absolutely unflinching, incredibly depressing, and yet I find it strangely life-affirming. Somebody quick translate the rest of his stuff...

Labels:

crime,

elizabeth hand,

t. jefferson parker,

thomas glavinic

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Crime Roundup

Hmm. This is the time of year when I generally make myself a giant pile of crime novels and plough through them with something close to ecstasy. But so far this summer there have been several piles, and the ecstasy has failed to materialize. I was never terribly hopeful about the state of crime fiction in general, but has writing in this genre gotten worse lately? Even a few well-known writers whose work I have repeatedly been assured I would love, and the reading of whom I had been holding off for the right moment, have disappointed.

One of them was George Pelecanos, whose The Night Gardener I actually quite liked. But then I turned to Right As Rain, one of the celebrated Derek Strange/Terry Quinn novels. I have to admit that I found it unbearably sanctimonious--the subject of these novels is race, and Pelecanos wields his Limbaughvian liberal straw men with embarrassing clumsiness, congratulating himself at every turn as, simultaneously, his characters emit angry speeches about white liberals who congratulate themselves at every turn. It's put me off this novelist entirely, in spite of my appreciation for the other book, which is really very skillful in its portrait of the social complexities of Washington, D.C.

Another letdown came in the form of Benjamin Black's novella The Lemur. I didn't mind the first novel by this writer, alter ego of the literary novelist John Banville, but here, in this shortened form, Black appears to have forgotten how to tell a story. The protagonist, a sour middle-aged man named John Glass, used to be a crack reporter. Now, he's married to an heiress he despises and has been hired to write his ex-CIA father-in-law's biography. He hires a researcher, the researcher finds out something, and then is murdered. Then there's eighty pages of people having the same inconclusive conversation over and over--Glass's mistress, a homicide detective, a jive-talkin' black journalist, the researcher's girlfriend--and then you find out the deadly information. There are never any clues, no gradual unveiling of detail. Instead, there are just a bunch of assholes--yes, every single character is a nasty, selfish, morally corrupt dullard--and a lot of descriptions of the wind in the trees. The book is weirdly static. Maybe it worked in its original incarnation as a serial in the New York Times Magazine, but here, it's a slog at 132 pages.

Worse yet was Will Lavender's Obedience, a book with a great premise: a college professor assigns his ethics class to solve a crime that has yet to be committed--and the crime turns out, quite possibly, to be real. Here's the passage, on page 55, that made me give up on this dreadful novel--in this scene, Dennis, an irresistebly charming young Republican, is being seduced by the Dean's wife:

Wow. Now that's bad.

I did actually manage to enjoy two crime novels over the past couple of months. One is the new one from Sweden's Hakan Nesser, Mind's Eye, which pits Inspector Van Veeteren against an open-and-shut case that doesn't make any sense. It's dark and witty and filled with that great Scandinavian winking ennui--no masterpiece, but well-crafted, gripping, and refreshingly un-full of itself. The other good one is Stephen Carter's bestselling The Emperor of Ocean Park. I'm a little late to the party on this one, but Carter, a Yale law professor, appears to have managed to become an excellent novelist in his spare time. The book is a political thriller by way of Richard Ford or Jane Smiley--a wise, self-deprecating narrator; many smart social insights; nice, long sentences; wonderful characters. In the end, it's a little long and implausible, but it's hard to begrudge Carter the opportunity to stretch his limbs, the prose is so thoroughly enjoyable. I should add that Carter is writing about race, too--his fictional D.C. family is black--and he kicks Pelecanos's ass on the subject. I've got Carter's second book queued up and ready to go, for when I finish this new James Wood thing (How Fiction Works), which I will address in a future post. Short version: it's superb, so far. I admire rather than like Wood's reviewing, but this book is both smart and personable. More soon.

One of them was George Pelecanos, whose The Night Gardener I actually quite liked. But then I turned to Right As Rain, one of the celebrated Derek Strange/Terry Quinn novels. I have to admit that I found it unbearably sanctimonious--the subject of these novels is race, and Pelecanos wields his Limbaughvian liberal straw men with embarrassing clumsiness, congratulating himself at every turn as, simultaneously, his characters emit angry speeches about white liberals who congratulate themselves at every turn. It's put me off this novelist entirely, in spite of my appreciation for the other book, which is really very skillful in its portrait of the social complexities of Washington, D.C.

Another letdown came in the form of Benjamin Black's novella The Lemur. I didn't mind the first novel by this writer, alter ego of the literary novelist John Banville, but here, in this shortened form, Black appears to have forgotten how to tell a story. The protagonist, a sour middle-aged man named John Glass, used to be a crack reporter. Now, he's married to an heiress he despises and has been hired to write his ex-CIA father-in-law's biography. He hires a researcher, the researcher finds out something, and then is murdered. Then there's eighty pages of people having the same inconclusive conversation over and over--Glass's mistress, a homicide detective, a jive-talkin' black journalist, the researcher's girlfriend--and then you find out the deadly information. There are never any clues, no gradual unveiling of detail. Instead, there are just a bunch of assholes--yes, every single character is a nasty, selfish, morally corrupt dullard--and a lot of descriptions of the wind in the trees. The book is weirdly static. Maybe it worked in its original incarnation as a serial in the New York Times Magazine, but here, it's a slog at 132 pages.

Worse yet was Will Lavender's Obedience, a book with a great premise: a college professor assigns his ethics class to solve a crime that has yet to be committed--and the crime turns out, quite possibly, to be real. Here's the passage, on page 55, that made me give up on this dreadful novel--in this scene, Dennis, an irresistebly charming young Republican, is being seduced by the Dean's wife:

She stripped off the wet bathing suit and left it in a heap at her jeweled feet...She had shaved her pussy into a fine little arrow of fuzz...Before he knew it he was coming, losing himself in the frenzied wake [they're on a boat, see. -JRL], the sloshing sound of the cove now a roar, Elizabeth with her head thrown back on top of him and her tits cupped in her own hands.

Wow. Now that's bad.

I did actually manage to enjoy two crime novels over the past couple of months. One is the new one from Sweden's Hakan Nesser, Mind's Eye, which pits Inspector Van Veeteren against an open-and-shut case that doesn't make any sense. It's dark and witty and filled with that great Scandinavian winking ennui--no masterpiece, but well-crafted, gripping, and refreshingly un-full of itself. The other good one is Stephen Carter's bestselling The Emperor of Ocean Park. I'm a little late to the party on this one, but Carter, a Yale law professor, appears to have managed to become an excellent novelist in his spare time. The book is a political thriller by way of Richard Ford or Jane Smiley--a wise, self-deprecating narrator; many smart social insights; nice, long sentences; wonderful characters. In the end, it's a little long and implausible, but it's hard to begrudge Carter the opportunity to stretch his limbs, the prose is so thoroughly enjoyable. I should add that Carter is writing about race, too--his fictional D.C. family is black--and he kicks Pelecanos's ass on the subject. I've got Carter's second book queued up and ready to go, for when I finish this new James Wood thing (How Fiction Works), which I will address in a future post. Short version: it's superb, so far. I admire rather than like Wood's reviewing, but this book is both smart and personable. More soon.

Monday, February 18, 2008

Self's Deception

I picked up a copy of this Bernhard Schlink mystery at Rhian's store the other day, because it has a blurb on the back from Håkan Nesser, whose The Return I really got into last year. I'd glanced at Schlink's books from time to time, figured I might like them, then somehow managed not to actually read any. Finally this week I read Self's Deception.

Not at all what I expected, though I don't know what I expected. Schlink can really write, and this book diverts from forumla in several ways, most prominently among them his detective, Gerhard Self, who is a dyspeptic 69-year-old who wheezes walking up the stairs. Self is prone to wonderfully dry asides, like this one, which he issues after wearily observing a Heidelberg street scene:

It's a nice change of pace from the usual hard-drinking, self-loathing gumshoe of pretty much every other mystery series out there, even the good ones. Self is in fact rather self-satisfied, a hedonist at heart, the kind of guy who spends his first day in jail (having aided a suspected terrorist in escaping to France) thusly: "I ate a few of the pretzels with some cheese and apples, drank the Barolo, and read Gottfried Keller."

Evidently prison isn't so bad, in Germany. In any event, I recommend this book--although the mystery itself is only somewhat interesting, and Self's deadpan delivery eventually becomes--not boring, not irritating, but uninspiring--and it's taken me more than a week to get to the end. Self's Deception is a novel I've been happy, every day, to get back to, but not exactly anguished to put down for the night.

Not at all what I expected, though I don't know what I expected. Schlink can really write, and this book diverts from forumla in several ways, most prominently among them his detective, Gerhard Self, who is a dyspeptic 69-year-old who wheezes walking up the stairs. Self is prone to wonderfully dry asides, like this one, which he issues after wearily observing a Heidelberg street scene:

I find the tide of strolling consumers in pedestrian areas no more agreeable, either aesthetically or morally, than comrades on parade or soldiers on the march. But I have grave doubts that I will live to see Heidelberg's main street once again filled with cheerfully ringing trams, cars honking happily, and related, bustling people hurrying to places where they have something to do, and not simply to places where there's something to see, something to nibble at, or something to buy.

It's a nice change of pace from the usual hard-drinking, self-loathing gumshoe of pretty much every other mystery series out there, even the good ones. Self is in fact rather self-satisfied, a hedonist at heart, the kind of guy who spends his first day in jail (having aided a suspected terrorist in escaping to France) thusly: "I ate a few of the pretzels with some cheese and apples, drank the Barolo, and read Gottfried Keller."

Evidently prison isn't so bad, in Germany. In any event, I recommend this book--although the mystery itself is only somewhat interesting, and Self's deadpan delivery eventually becomes--not boring, not irritating, but uninspiring--and it's taken me more than a week to get to the end. Self's Deception is a novel I've been happy, every day, to get back to, but not exactly anguished to put down for the night.

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

Murdaland!

Tonight's post will be brief, as I'm busy reading Rhian's post-apocalyptic lesbian gang novel. Man, this stuff is foxy--wait 'til you see what they're getting up to in their caves! It is just TOO HOT FOR BANTAM DELL!

Meanwhile, I bring you news of a new magazine called Murdaland. It is, apparently, a haven for literary crime fiction, and its web site is lovingly embedded with scary noises. A colleague of mine gave me a copy of the first issue, and although I haven't read the whole thing, it seems pretty damned good so far.

Crime fiction lives and dies by the opening line, so let's see where we stand with Murdaland #1...

Rolo Diez: "Night falls and there's nowhere to go."

Anthony Neil Smith: "I wanted to plan the coolest funeral ever for my girlfriend."

Kaili Van Waiveren: "Meatball opens the door holding a knife."

J. D. Rhoades: "These days, they mostly used the backhoe."

Tristan Davies: "In the course of my job, I sometimes wear a Boy Scout uniform."

Who the hell are these people, and where have they been all my life? (To be fair, I have met Tristan Davies, but this is the first thing of his I've read.) It's funny, there are established literary writers here (Mary Gaitskill and Richard Bausch), but they resist the temptation to start off with a corker...as much as I admire them, I'll be reading their stories last. Fast and lurid wins the race.

Go subscribe to this thing--its editors should be rewarded.

Meanwhile, I bring you news of a new magazine called Murdaland. It is, apparently, a haven for literary crime fiction, and its web site is lovingly embedded with scary noises. A colleague of mine gave me a copy of the first issue, and although I haven't read the whole thing, it seems pretty damned good so far.

Crime fiction lives and dies by the opening line, so let's see where we stand with Murdaland #1...

Rolo Diez: "Night falls and there's nowhere to go."

Anthony Neil Smith: "I wanted to plan the coolest funeral ever for my girlfriend."

Kaili Van Waiveren: "Meatball opens the door holding a knife."

J. D. Rhoades: "These days, they mostly used the backhoe."

Tristan Davies: "In the course of my job, I sometimes wear a Boy Scout uniform."

Who the hell are these people, and where have they been all my life? (To be fair, I have met Tristan Davies, but this is the first thing of his I've read.) It's funny, there are established literary writers here (Mary Gaitskill and Richard Bausch), but they resist the temptation to start off with a corker...as much as I admire them, I'll be reading their stories last. Fast and lurid wins the race.

Go subscribe to this thing--its editors should be rewarded.

Thursday, September 6, 2007

Compulsory Crappy Crime Novel Elements

*sigh* I'm not going to bother naming the incredibly boring mystery I just gave up reading in the middle of that has inspired this post, but here is a partial list of all the mandatory elements of crappy crime fiction. Feel free to add your own!

- If a detective is about to do something, but then is called away and never gets around to it, then that thing must be the most important thing in the whole book.

- The detective must like music, and when he/she listens to it, it must be identified. If it is jazz, it must be lushly described, and the detective must muse about how he/she personally relates to Sonny Rollins or Miles Davis or Bill Evans or whomever. THE RANKIN EXCEPTION: Detective may not like music as long as his partner does, and HER music is lushly described and named, so that detective can express his distaste for it in an informed manner.

- If there is a crazy person wandering around uttering nonsense, that nonsense must actually hold the clue that solves the crime!

- The hunter must become the hunted.

- Serial killers must be brilliant and love taunting cops.

- Any characters who are writers, artists, photographers, or people with any creative talent at all must be secretly vain and shallow, and their art a crass attempt to draw attention to themselves.

- Detective cannot be happily married.

- Detective cannot ever experience feelings of joy or even vague personal well-being.

- When a dead body is found, its odor must first be "unmistakeable," then "indescribable." Bonus points if the smell then "assaults" someone's "nostrils."

- When the medical examiner arrives, he/she must be asked to make a snap judgement, then must reply that this is impossible, then do it anyway and be exactly right. Later, the autopsy report cannot be delivered by phone, fax, or e-mail. Instead, the detective must visit the morgue and discuss the case over the eviscerated corpse. At this time, the ME should be eating a sandwich.

- All recurring underworld nemeses must at some point say to detective, "We're not so different, you and me."

- Hunches are always right.

- Detectives' strategic encroachments upon citizens' civil liberties must be frowned upon by preening, camera-hungry police chiefs, but then must be proven to be the only real way to "get things done."

- Detective may accidentally kill somebody, if the victim "deserved it"; however, detective must still beat him/herself up over it.

- If detective has children, they must be estranged.

- Detective must have special tavern/bar hideaway, preferably named after an animal.

- Witnesses who can't remember lots of details are idiots.

BONUS POINTS FOR ADDING THESE NONVITAL BUT USEFUL ELEMENTS!

- Detective staring into body of water

- Detective attending victim's funeral and gleaning valuable information

- Detective going through the "murder book" just one more time

- Street festival, town celebration, or huge benefit concert

- Big storm

- Detective's apartment ransacked and threatening message left behind

- Cryptic phone call that cuts out abruptly

- Effusive acknowledgements section naming dozens of helpful police officers

- Cover image of person in fog, hunched in a trenchcoat

- Seven-figure advance

- If a detective is about to do something, but then is called away and never gets around to it, then that thing must be the most important thing in the whole book.

- The detective must like music, and when he/she listens to it, it must be identified. If it is jazz, it must be lushly described, and the detective must muse about how he/she personally relates to Sonny Rollins or Miles Davis or Bill Evans or whomever. THE RANKIN EXCEPTION: Detective may not like music as long as his partner does, and HER music is lushly described and named, so that detective can express his distaste for it in an informed manner.

- If there is a crazy person wandering around uttering nonsense, that nonsense must actually hold the clue that solves the crime!

- The hunter must become the hunted.

- Serial killers must be brilliant and love taunting cops.

- Any characters who are writers, artists, photographers, or people with any creative talent at all must be secretly vain and shallow, and their art a crass attempt to draw attention to themselves.

- Detective cannot be happily married.

- Detective cannot ever experience feelings of joy or even vague personal well-being.

- When a dead body is found, its odor must first be "unmistakeable," then "indescribable." Bonus points if the smell then "assaults" someone's "nostrils."

- When the medical examiner arrives, he/she must be asked to make a snap judgement, then must reply that this is impossible, then do it anyway and be exactly right. Later, the autopsy report cannot be delivered by phone, fax, or e-mail. Instead, the detective must visit the morgue and discuss the case over the eviscerated corpse. At this time, the ME should be eating a sandwich.

- All recurring underworld nemeses must at some point say to detective, "We're not so different, you and me."

- Hunches are always right.

- Detectives' strategic encroachments upon citizens' civil liberties must be frowned upon by preening, camera-hungry police chiefs, but then must be proven to be the only real way to "get things done."

- Detective may accidentally kill somebody, if the victim "deserved it"; however, detective must still beat him/herself up over it.

- If detective has children, they must be estranged.

- Detective must have special tavern/bar hideaway, preferably named after an animal.

- Witnesses who can't remember lots of details are idiots.

BONUS POINTS FOR ADDING THESE NONVITAL BUT USEFUL ELEMENTS!

- Detective staring into body of water

- Detective attending victim's funeral and gleaning valuable information

- Detective going through the "murder book" just one more time

- Street festival, town celebration, or huge benefit concert

- Big storm

- Detective's apartment ransacked and threatening message left behind

- Cryptic phone call that cuts out abruptly

- Effusive acknowledgements section naming dozens of helpful police officers

- Cover image of person in fog, hunched in a trenchcoat

- Seven-figure advance

Tuesday, August 21, 2007

Karin Fossum's "Black Seconds"

I'd really been looking forward to this new Karin Fossum novel, the fifth of her eight books to be translated into English from her native Norwegian, as the last one, Beloved Poona (disappointingly published in the UK as Don't Look Back and here as The Indian Bride) was as satisfying a literary portrait of a small town as I've ever seen, and reminded me at times of, yes, even Alice Munro. So it's a surprise to discover that this book (translated by Charlotte Barslund) is the most traditional police procedural Fossum has produced, residing for much of its length in the mind of its austere protagonist, Inspector Conrad Sejer.

Not that I have a problem with that. I am, after all, a crime buff, and Fossum is quite rightly known as a crime novelist. Still, she had been playing with the bounds of the genre, and it was faintly disappointing to see her pulling back.

That said, the book itself is not remotely disappointing--in fact it's really good. A girl goes missing, inexplicably, in broad daylight, and a week of searching turns up nothing. That's the setup. Unlike most crime novelists, Fossum doesn't play it as a whodunit--we very quickly meet three characters who are certainly involved in the girl's disappearance, and there is never any indication that this is some kind of feint on the author's part. And it isn't. Rather, the novel unfolds as a howdunit--we know more than Sejer, but as we get closer to the end, his knowledge catches up to ours, and we learn the key facts by his side. There are no nasty shocks, only the fascination of watching complex characters admit to themselves at last what they have done.

Fossum does something in her books that I absolutely despise in other writers--she allows us into the minds of the criminals, who just happen not to be thinking of the answer to the mystery when we stop by. This tactic can seem terribly manipulative and opportunistic, but for some reason it doesn't bother me with Fossum. In Beloved Poona this makes a certain kind of sense, as the guilty party is keeping the secret even from him/herself, in a psychologically plausible way. Here, though, the line is a little blurrier, and I felt a few times that she was cheating just a bit.

But perhaps that's merely a byproduct of my intimacy with the traditional police procedural, where the solution to the crime usually is the point, and the psychological depth of the characters of less importance. There, this move really is a cheat. Here, though, I was surprised to find myself happily going along for the ride. Particularly commendable in this book is the way Fossum brings to life one particular man, an introverted and possibly autistic eccentric in his fifties, whose sessions with Sejer are truly exciting and convincing.

So, not what I expected, but I'm very satisfied. Recommended.

Not that I have a problem with that. I am, after all, a crime buff, and Fossum is quite rightly known as a crime novelist. Still, she had been playing with the bounds of the genre, and it was faintly disappointing to see her pulling back.

That said, the book itself is not remotely disappointing--in fact it's really good. A girl goes missing, inexplicably, in broad daylight, and a week of searching turns up nothing. That's the setup. Unlike most crime novelists, Fossum doesn't play it as a whodunit--we very quickly meet three characters who are certainly involved in the girl's disappearance, and there is never any indication that this is some kind of feint on the author's part. And it isn't. Rather, the novel unfolds as a howdunit--we know more than Sejer, but as we get closer to the end, his knowledge catches up to ours, and we learn the key facts by his side. There are no nasty shocks, only the fascination of watching complex characters admit to themselves at last what they have done.

Fossum does something in her books that I absolutely despise in other writers--she allows us into the minds of the criminals, who just happen not to be thinking of the answer to the mystery when we stop by. This tactic can seem terribly manipulative and opportunistic, but for some reason it doesn't bother me with Fossum. In Beloved Poona this makes a certain kind of sense, as the guilty party is keeping the secret even from him/herself, in a psychologically plausible way. Here, though, the line is a little blurrier, and I felt a few times that she was cheating just a bit.

But perhaps that's merely a byproduct of my intimacy with the traditional police procedural, where the solution to the crime usually is the point, and the psychological depth of the characters of less importance. There, this move really is a cheat. Here, though, I was surprised to find myself happily going along for the ride. Particularly commendable in this book is the way Fossum brings to life one particular man, an introverted and possibly autistic eccentric in his fifties, whose sessions with Sejer are truly exciting and convincing.

So, not what I expected, but I'm very satisfied. Recommended.

Wednesday, August 8, 2007

Foreign Crime Roundup

It's time once again to review the latest in foreign crime novels--as Rhian mentioned, we're at the shore, and so I had Amazon (sorry, independent bookstore supporters--if you can find somebody else who can get my the British books I crave, I will switch in a heartbeat) send me a few new ones for perusal on the beach.

(And let me say first that I am not actually reading these on the beach. I love the ocean, but I hate the beach--my skin is the color of an oak desk even in January and I don't need a tan. So it's off to the beach for swimming, and back to the air-conditioned rental for books.)

Anyway, I'm reading four new novels, two of which I'll discuss in this post--Hakan Nesser's The Return and The New Ruth Rendell, Not In The Flesh. The Rendell first--this book is the latest Chief Inspector Wexford mystery, and I am sad to say that, while it's pretty entertaining, it does not quite measure up to her best. The supporting cast of this long-running series has become rather cartoonish in this installment, and--in a very, very un-Rendellian mistake--an obvious clue appears halfway through that gives it all away. There are other Wexford books in which this seems to happen, but it's always a trick--the real answer is tucked away somewhere you would never have thought to look. This time, however, it's the real thing, and is something of a disappointment, though I'd pick middling Rendell over a lot of crime writers' best, any day. In addition, I'm not saying Rendell has lost her touch--the last Barbara Vine book was one of my favorites ever. If it's Wexford you want, though, go check out Kissing The Gunner's Daughter or Road Rage.

More satisfying is the Nesser, which I'd had no particular expectation for--the first of this Swede's novels to be translated, Borkmann's Point, was pretty decent, but not among my favorite recent Scandanavian mysteries. This new one is terrific, though. Inspector Van Veeteren, the series' gruff protagonist, is in the hospital having a length of intestine removed, and takes it upon himself to solve the crime from his bed. A man convicted of two murders is released from prison and is soon murdered himself; the subsequent investigation uncovers information that leads Van Veeteren to suspect that the man might be innocent of the first two killings. The book is smart, philosophical, and dryly written, and I was utterly blindsided by the shocking ending.

I just cracked the new Arnaldur Indridason, and have the latest Karin Fossum on deck--the latter is one of my favorite writers currently and I've saved her for last. I'll post about them in the coming days.

(And let me say first that I am not actually reading these on the beach. I love the ocean, but I hate the beach--my skin is the color of an oak desk even in January and I don't need a tan. So it's off to the beach for swimming, and back to the air-conditioned rental for books.)

Anyway, I'm reading four new novels, two of which I'll discuss in this post--Hakan Nesser's The Return and The New Ruth Rendell, Not In The Flesh. The Rendell first--this book is the latest Chief Inspector Wexford mystery, and I am sad to say that, while it's pretty entertaining, it does not quite measure up to her best. The supporting cast of this long-running series has become rather cartoonish in this installment, and--in a very, very un-Rendellian mistake--an obvious clue appears halfway through that gives it all away. There are other Wexford books in which this seems to happen, but it's always a trick--the real answer is tucked away somewhere you would never have thought to look. This time, however, it's the real thing, and is something of a disappointment, though I'd pick middling Rendell over a lot of crime writers' best, any day. In addition, I'm not saying Rendell has lost her touch--the last Barbara Vine book was one of my favorites ever. If it's Wexford you want, though, go check out Kissing The Gunner's Daughter or Road Rage.

More satisfying is the Nesser, which I'd had no particular expectation for--the first of this Swede's novels to be translated, Borkmann's Point, was pretty decent, but not among my favorite recent Scandanavian mysteries. This new one is terrific, though. Inspector Van Veeteren, the series' gruff protagonist, is in the hospital having a length of intestine removed, and takes it upon himself to solve the crime from his bed. A man convicted of two murders is released from prison and is soon murdered himself; the subsequent investigation uncovers information that leads Van Veeteren to suspect that the man might be innocent of the first two killings. The book is smart, philosophical, and dryly written, and I was utterly blindsided by the shocking ending.

I just cracked the new Arnaldur Indridason, and have the latest Karin Fossum on deck--the latter is one of my favorite writers currently and I've saved her for last. I'll post about them in the coming days.

Saturday, May 12, 2007

Another Swedish Mystery!

OK, you know what? I'm gonna keep on posting about these Swedish crime novels until you commenters start readin' 'em.

OK, you know what? I'm gonna keep on posting about these Swedish crime novels until you commenters start readin' 'em.The latest one I've discovered is The Princess of Burundi, by Kjell Eriksson, which won the Swedish Crime Academy's best novel award in, apparently, 1992. Why did it take so long to translate this book? I don't know. The translator is the able Ebba Segerberg, who translates the Henning Mankell novels, which I also like, but not as much as this one. The book is a rambling murder mystery; its point of view is roving, sticking mostly with a small cast of detectives, including the brooding Ola Haver and the regretful, obsessive Ann Lindell. It feels very much like it was plucked from the middle of a series, and indeed, there's another one out in English, which I've got on order.

Eriksson's writing is straightforward, dry, and egalitarian; the lives of the criminals and their pursuers are weighted equally, to fine effect. I usually hate the "mind of the killer" nonsense that most crime writers feel obliged to include in their books--it is almost invariably presented opportunistically and in direct violation of the rules of narrative, so that the bad guys just happen not to be thinking of all the vital facts of the case that you're not yet supposed to know--but when Eriksson does it, it's great, and it also isn't quite what you think it is, anyway. Plus it doesn't break the rules.

Henning Mankell has been called the heir to my favorite crime writers, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, but I think Eriksson, at least judging by this book, is closer to their ideal--like them, he is concerned with life as it is actually lived, and the idea that mystery is an inherent part of it, rather than with mystery as an aberration.

Friday, March 16, 2007

T. Jefferson Parker

Crime again, I'm afraid. When I'm trying to write a novel, I don't like to read other literary novels--their style starts bleeding into mine. So it's genre fiction--and Proust--until summer arrives.

(Yeah, Proust, in the new Penguin translations. With my book group, I'm 4/7ths through In Search of Lost Time, as it's now more suitably called, and I'll post about it when I've burrowed a few hundred pages into The Prisoner.)

Anyway, this week's crime novel is the new T. Jefferson Parker, Storm Runners. Parker's an odd phenomenon. He does indeed write police procedurals, and does have a couple of recurring characters, but his best stuff is generally the one-offs. (That Wikipedia entry I linked him to, by the way, is full of errors--not all his books are, in fact, police procedurals.) This is the opposite of what generally holds true with crime writers, which is that their series books are better than the one-offs (I'm thinking here of the non-Barbara Vine Ruth Rendell, and Michael Connelly, whose non-Harry-Bosch books have never done much for me).

Probably the best of Parker's novels is Silent Joe, a book about a policeman who gets dangerously entangled in the web of connections that bind cops and criminals. And come to think of it, the new one's about the same thing. And they both have vengeance as a theme, go figure.

But they're not regular thrillers, honest--they don't glorify violence, or vengeance for that matter, and they don't manipulate with easy emotion. Storm Runners (not a terrific title, I'm aware) is about a cop whose family has been killed by a Mexican mobster who was both a childhood friend and a former lover of his late wife. The cop, Matt Stromsoe, takes two years to recover, physically and emotionally, from the bombing, and gets a job as bodyguard to a Fox News weather lady who just happens to be monumentally hot and has also figured out how to make rain...so of course the head honcho of the Department of Water and Power, who has for years controlled the city's water supply, needs to have her killed, so as to preserve his importance, and he ends up getting mixed up with the same mobster who killed Stromsoe's family.

Wow, that sounds really dumb. But it's not! It's in the wild and implausible details that Parker's novels really cook--there, and in his prose, which is restrained, skillful, and marvelously unpurple. No expository dialogue, no passionate bad guy speeches, no churning logorrhoea about the blackness of the soul. Just good writing, solid pacing, strong characters, and lots of geeky information about rivers, weather, and the complex inner workings of prison life and Latino gangs. Plus, he's got the "first-intial/middle-name/last-name" mojo working, which as we know is the mark of brilliance.

(Yeah, Proust, in the new Penguin translations. With my book group, I'm 4/7ths through In Search of Lost Time, as it's now more suitably called, and I'll post about it when I've burrowed a few hundred pages into The Prisoner.)

Anyway, this week's crime novel is the new T. Jefferson Parker, Storm Runners. Parker's an odd phenomenon. He does indeed write police procedurals, and does have a couple of recurring characters, but his best stuff is generally the one-offs. (That Wikipedia entry I linked him to, by the way, is full of errors--not all his books are, in fact, police procedurals.) This is the opposite of what generally holds true with crime writers, which is that their series books are better than the one-offs (I'm thinking here of the non-Barbara Vine Ruth Rendell, and Michael Connelly, whose non-Harry-Bosch books have never done much for me).

Probably the best of Parker's novels is Silent Joe, a book about a policeman who gets dangerously entangled in the web of connections that bind cops and criminals. And come to think of it, the new one's about the same thing. And they both have vengeance as a theme, go figure.

But they're not regular thrillers, honest--they don't glorify violence, or vengeance for that matter, and they don't manipulate with easy emotion. Storm Runners (not a terrific title, I'm aware) is about a cop whose family has been killed by a Mexican mobster who was both a childhood friend and a former lover of his late wife. The cop, Matt Stromsoe, takes two years to recover, physically and emotionally, from the bombing, and gets a job as bodyguard to a Fox News weather lady who just happens to be monumentally hot and has also figured out how to make rain...so of course the head honcho of the Department of Water and Power, who has for years controlled the city's water supply, needs to have her killed, so as to preserve his importance, and he ends up getting mixed up with the same mobster who killed Stromsoe's family.

Wow, that sounds really dumb. But it's not! It's in the wild and implausible details that Parker's novels really cook--there, and in his prose, which is restrained, skillful, and marvelously unpurple. No expository dialogue, no passionate bad guy speeches, no churning logorrhoea about the blackness of the soul. Just good writing, solid pacing, strong characters, and lots of geeky information about rivers, weather, and the complex inner workings of prison life and Latino gangs. Plus, he's got the "first-intial/middle-name/last-name" mojo working, which as we know is the mark of brilliance.

Tuesday, March 6, 2007

Out, Again

I posted a few days ago about Natsuo Kirino's crime novel Out, and while I said I liked it pretty well, I kind of condemned its writing style and plot with faint praise. I hadn't finished it at the time, though, and now I feel bad.

Having read the whole thing now, I have to admit that Out is a really strange, really interesting book. At the halfway point, Kirino appeared to be moving toward a number of familiar tropes of the genre--the women who covered up the murder of their friend's husband had inadvertently let out a few details, several unsavory figures got wind of their deed, and the police seemed to be closing in. I was certain there would be some blackmail, some betrayal, some retribution, in the classic style.

I was completely wrong. The plot takes a weird, surprising, and ultimately quite plausible turn which I won't reveal here. But the story picked up steam so completely at that point that I would later be amazed that I had once considered not bothering to finish.

As for the writing style, I can't decide. It's unadorned, which I usually like. But its character development is very expository--feelings are rather clinically described and explained, instead of being illustrated with action and dialogue. Ordinarily this would bother me, but by the end of Out I wondered if perhaps this is simply part of the character of Japanese fiction. Kirino's the only Japanese novelist I've read (save for Haruki Murakami, who I think of as more of a cross-cultural, "international" writer)...can anyone weigh in on this issue?

Anyway, my apologies--Out is a terrific book, especially the second half!

Having read the whole thing now, I have to admit that Out is a really strange, really interesting book. At the halfway point, Kirino appeared to be moving toward a number of familiar tropes of the genre--the women who covered up the murder of their friend's husband had inadvertently let out a few details, several unsavory figures got wind of their deed, and the police seemed to be closing in. I was certain there would be some blackmail, some betrayal, some retribution, in the classic style.

I was completely wrong. The plot takes a weird, surprising, and ultimately quite plausible turn which I won't reveal here. But the story picked up steam so completely at that point that I would later be amazed that I had once considered not bothering to finish.

As for the writing style, I can't decide. It's unadorned, which I usually like. But its character development is very expository--feelings are rather clinically described and explained, instead of being illustrated with action and dialogue. Ordinarily this would bother me, but by the end of Out I wondered if perhaps this is simply part of the character of Japanese fiction. Kirino's the only Japanese novelist I've read (save for Haruki Murakami, who I think of as more of a cross-cultural, "international" writer)...can anyone weigh in on this issue?

Anyway, my apologies--Out is a terrific book, especially the second half!

Labels:

crime,

haruki murakami,

japan,

natsuo kirino,

translations

Saturday, March 3, 2007

Bulletin: Crime In Translation

I say "Bulletin," because I'm probably going to be doing this every once in a while. I am big into crime in translation, even above and beyond Crime & Punishment.

This week I finished Åsa Larsson's latest, The Blood Spilt. Larsson is Swedish, and her first book, Sun Storm, was excellent; in it, a young lawyer gets caught up in the aftermath of a ritualistic murder that occurs in a church in her rural home town. This time, however, is totally different--the same lawyer accidentally gets caught up in a completely different ritual murder in a church, this one a few towns down the river from her rural home town.

No, really. Wacky coincidence, huh? Surely the next book won't be...

That's the blurb for Larsson's next book, and I don't know if I'm terribly interested in returning to Kiruna with Rebecka, to be honest. I was certainly happy to be there with her this time, though--The Blood Spilt is a fine book. Larsson is essentially a literary novelist disguised as a crime writer; you should read this book not for the plausibility of its plot but for its small, careful observations of small town life. I wish more American crime writers would take this tack--crime is a social and psychological phenomenon, the result of friction between the individual and the society, not some Lord-Of-The-Rings-style battle between good and evil: literary fiction is the perfect vehicle for it.

The other thing I've been enjoying--I'm about halfway through--is Natsuo Kirino's Out, which Junot Diaz recommended to me a couple of weeks ago when he was in town. It's the story of four women who work together at a boxed-lunch factory in Tokyo; when one of them murders her abusive husband, the others help out by chopping him up and distributing the pieces all over town. It's a hideously gruesome book, and the writing is nothing special...but its portrayal of Japanese working-class life is stunning, and unique among books I've read. These women have to change their mother-in-law's diapers, fend off credit agencies, talk rapists out of attacking them, and endure the demeaning insults of their depressed husbands as they cover up the murder; the shrewdness of their deception is only possible because they've sharpened their chops fending off a society that despises them. Heavy going, but fascinating.

I posted this early by mistake--sorry if you saw it getting cut off in mid-sentence!

This week I finished Åsa Larsson's latest, The Blood Spilt. Larsson is Swedish, and her first book, Sun Storm, was excellent; in it, a young lawyer gets caught up in the aftermath of a ritualistic murder that occurs in a church in her rural home town. This time, however, is totally different--the same lawyer accidentally gets caught up in a completely different ritual murder in a church, this one a few towns down the river from her rural home town.

No, really. Wacky coincidence, huh? Surely the next book won't be...

But to help her friend, and to find the real killer of a man she once adored and is now not sure she ever knew, Rebecka must relive the darkness she left behind in Kiruna, delve into a sordid conspiracy of deceit, and confront a killer whose motives are dark and impossible to guess ...

That's the blurb for Larsson's next book, and I don't know if I'm terribly interested in returning to Kiruna with Rebecka, to be honest. I was certainly happy to be there with her this time, though--The Blood Spilt is a fine book. Larsson is essentially a literary novelist disguised as a crime writer; you should read this book not for the plausibility of its plot but for its small, careful observations of small town life. I wish more American crime writers would take this tack--crime is a social and psychological phenomenon, the result of friction between the individual and the society, not some Lord-Of-The-Rings-style battle between good and evil: literary fiction is the perfect vehicle for it.

The other thing I've been enjoying--I'm about halfway through--is Natsuo Kirino's Out, which Junot Diaz recommended to me a couple of weeks ago when he was in town. It's the story of four women who work together at a boxed-lunch factory in Tokyo; when one of them murders her abusive husband, the others help out by chopping him up and distributing the pieces all over town. It's a hideously gruesome book, and the writing is nothing special...but its portrayal of Japanese working-class life is stunning, and unique among books I've read. These women have to change their mother-in-law's diapers, fend off credit agencies, talk rapists out of attacking them, and endure the demeaning insults of their depressed husbands as they cover up the murder; the shrewdness of their deception is only possible because they've sharpened their chops fending off a society that despises them. Heavy going, but fascinating.

I posted this early by mistake--sorry if you saw it getting cut off in mid-sentence!

Labels:

Åsa Larsson,

crime,

japan,

natsuo kirino,

translations

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

Hard Case Crime

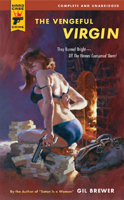

So is anybody else digging the Hard Case Crime series? This is a new-ish crime fiction imprint that puts out a book every month; you can arrange to have a standing order charged to your credit card, and you'll just get the new book in the mail. The books look and feel fantastic--mass market paperbacks, just the right size, the title and author printed in bold sans serif type in yellow and black on a white spine, and an outrageously lurid fifties-retro painting on the cover.

So is anybody else digging the Hard Case Crime series? This is a new-ish crime fiction imprint that puts out a book every month; you can arrange to have a standing order charged to your credit card, and you'll just get the new book in the mail. The books look and feel fantastic--mass market paperbacks, just the right size, the title and author printed in bold sans serif type in yellow and black on a white spine, and an outrageously lurid fifties-retro painting on the cover.Some of the books are new; most are reissues. There are a few surprises--a Stephen King novella, a reprint of Madison Smartt Bell's Straight Cut, which is hardly what you'd call hard-boiled. And honestly, some of the books are kind of bad. It hardly matters, though. There are enough gems to keep you excited for the next one to show up, and the entire operation feels like a throwback to a bygone era--not just the books themselves, but the idea of getting them in the mail, direct from the publisher.

If you'd like to read a book written by a woman, by the way, forget it. So far there are precisely zero. If, however, you like the idea of getting shot in the head by one, especially a totally hot one in her underwear, then you're in business.

On a related note, there's a part of me that wishes everything were a mass market paperback. I'd happily pay a little extra for nice, acid-free paper, but I don't enjoy paying for hard covers and rough-cut pages--and I especially don't enjoy thinking of all the people who don't bother buying my own stuff when it comes out because it costs twenty-five dollars. I wish every decent book cost ten bucks. I wish every decent book could fit in your jeans pocket.

End of rant.

Monday, January 15, 2007

The Detective as a Purifying Force

I'm about halfway through this new-ish translation of Crime and Punishment I posted about a couple of days ago, and came to the bit in the middle where Porfiry, the investigator, shows up. I'd forgotten how surprising this scene is--Raskolnikov and his friend Razumikhin go to Porfiry's apartment in order for Raskolnikov to see if he can recover the items he pawned with the murdered pawnbroker (murdered, of course, by Raskolnikov himself). And after telling Raskolnikov that he can indeed recover the items, Porfiry says:

And a few moments later, he adds, "You are the only one"--that is, of the pawners--"who has not been so good as to pay us a visit."

The overall impression, which both Raskolnikov and the reader takes away from this conversation, is that Porfiry already knows Raskolnikov is the killer, and thus that his role is not to investigate the crime, but to serve as confessor to the criminal. He is the vessel into which the truth is supposed to be poured.

In a sense, every great literary detective is like this. The detective exists to receive the truth, and to know its implications. The possibility that this is so seems to mesmerize Raskolnikov--indeed, he keeps thinking Porfiry is winking at him, but is never entirely sure if this impression is real. The scene recasts Raskolnikov's supposed madness as a kind of spiritual dissonance, a moral imbalance. One thinks of President Bush's deer-in-the-headlights stare during his speech the other night, the gaze of a lunatic being dragged from his bunker into the light of day.

"Your things would not be lost in any event," he went on calmly and coldly, "because I've been sitting here a long time waiting for you."

And a few moments later, he adds, "You are the only one"--that is, of the pawners--"who has not been so good as to pay us a visit."

The overall impression, which both Raskolnikov and the reader takes away from this conversation, is that Porfiry already knows Raskolnikov is the killer, and thus that his role is not to investigate the crime, but to serve as confessor to the criminal. He is the vessel into which the truth is supposed to be poured.

In a sense, every great literary detective is like this. The detective exists to receive the truth, and to know its implications. The possibility that this is so seems to mesmerize Raskolnikov--indeed, he keeps thinking Porfiry is winking at him, but is never entirely sure if this impression is real. The scene recasts Raskolnikov's supposed madness as a kind of spiritual dissonance, a moral imbalance. One thinks of President Bush's deer-in-the-headlights stare during his speech the other night, the gaze of a lunatic being dragged from his bunker into the light of day.

Tuesday, January 9, 2007

Robert Wilson Tackles Terrorism

I'm a bit of a crime fiction fanatic, but the worst kind you can be: the kind who wants the writing to be awesome. I think I'm more disappointed by bad crime novels than by pretty much every other sort of bad novel, and more delighted by a good one than is perhaps healthy. A good police procedural can serve as a near-perfect metaphor for the process of creative inspiration; a bad one makes a mockery of discovery.

By and large I've gotten the most enjoyment out of Scandinavia, beginning with the Swedish husband-and-wife team of Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, who wrote what has to be the greatest detective series of all time, in the 1960's and 70's. Their ten-book run included the stunning The Laughing Policeman and the deeply interior and ultimately optimistic The Locked Room. And their successors, who include Henning Mankell, Karin Fossum, Ake Edwardsson, and Arnaldur Indridason, have also written a veritable library of absorbing mysteries.

But what I've most looked forward to lately has been whatever Robert Wilson has just published, particularly the books featuring Spanish police detective Javier Falcón. Wilson is British, and writes about everywhere but Britain; the Falcón books, set in Seville, are the most convincing, and the character the one, among Wilson's oeurve, with whom he seems most engaged. The new one, The Hidden Assassins, is probably my least favorite of the bunch, but it's still pretty good, and I recommend it.

In it, Falcón finds himself presiding over a bombing that appears to be the work of Islamic terrorists. The investigation, of course, reveals that the bombing isn't so straightforward as that. This is no surprise, of course--but what sets the novel apart is the way it demonstrates the deep complexity of terrorism itself, the multiplicity of its connections, the depth of its political opportunism, and the way it is enabled by those who benefit from its condemnation.

Throughout, we see how the bombing worms itself into the lives of Falcón's friends, family, and associates, and get to enjoy more of the smart, exhausted self-doubt that characterizes this most lachrymose of policemen. Wilson loves to use Falcón to turn the clichés of crime fiction inside out. Here, he knocks a dent in the storied power of intuition:

Nothing in this book seems remotely like laziness, though you could fault Wilson for his mountains of (admittedly fascinating) expository dialogue. Still, it's lovely not to have to throw a crime novel across the room, especially one as heavy as this one.

By and large I've gotten the most enjoyment out of Scandinavia, beginning with the Swedish husband-and-wife team of Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, who wrote what has to be the greatest detective series of all time, in the 1960's and 70's. Their ten-book run included the stunning The Laughing Policeman and the deeply interior and ultimately optimistic The Locked Room. And their successors, who include Henning Mankell, Karin Fossum, Ake Edwardsson, and Arnaldur Indridason, have also written a veritable library of absorbing mysteries.

But what I've most looked forward to lately has been whatever Robert Wilson has just published, particularly the books featuring Spanish police detective Javier Falcón. Wilson is British, and writes about everywhere but Britain; the Falcón books, set in Seville, are the most convincing, and the character the one, among Wilson's oeurve, with whom he seems most engaged. The new one, The Hidden Assassins, is probably my least favorite of the bunch, but it's still pretty good, and I recommend it.

In it, Falcón finds himself presiding over a bombing that appears to be the work of Islamic terrorists. The investigation, of course, reveals that the bombing isn't so straightforward as that. This is no surprise, of course--but what sets the novel apart is the way it demonstrates the deep complexity of terrorism itself, the multiplicity of its connections, the depth of its political opportunism, and the way it is enabled by those who benefit from its condemnation.

Throughout, we see how the bombing worms itself into the lives of Falcón's friends, family, and associates, and get to enjoy more of the smart, exhausted self-doubt that characterizes this most lachrymose of policemen. Wilson loves to use Falcón to turn the clichés of crime fiction inside out. Here, he knocks a dent in the storied power of intuition:

Falcón was surprised at himself. He'd been such a scientific investigator in the past, always keen to get his hands on autopsy reports and forensic evidence. Now he spent more time tuning in to his intuition. He tried to persuade himself that it was experience but sometimes it seemed like laziness.

Nothing in this book seems remotely like laziness, though you could fault Wilson for his mountains of (admittedly fascinating) expository dialogue. Still, it's lovely not to have to throw a crime novel across the room, especially one as heavy as this one.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)