It seems that certain art forms rise and fall over time -- or maybe all art forms do. The 60's were great for rock music, the 1600's for painting, etc. The 80's were definitely a wonderful time for the short story. Kicked off by Carver, the decade really just exploded with new and interesting voices: Laurie Moore, Charles Baxter, Amy Hempel, Grace Paley, Ann Beattie, Rick Bass, Richard Ford, etc.

Or do I just think that because I started reading short stories then, and was all pre-cynical and loving everything?

I feel like short stories are at a low ebb now, though there are some signs of strength and originality, like the quasi-science fiction stuff by Kelly Link. I'm not sure if the lack of short story energy is on the part of writers, readers, or publishers, or if it's just one of those cyclical things. Another possible explanation is that the personal essay and memoir have largely eclipsed fiction. If that's the case, then I guess that memoir has about two or three years to run its course, and then fiction -- including short fiction -- will rise again. (Hmm... that has a kind of "famous last words" ring about it...)

Meanwhile, according to the very cool blog Syntax of Things, February is SoTShoStoWriMo, or Syntax of Things Short Story Writing Month. I have been enjoying NaNoWriMo for a couple of years now, so maybe I'll give it a try. In any case, I highly suggest checking out the blog, as well as the other literary blogs we've linked to.

I certainly would love to see a short story renaissance.

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

Short Fiction in Serial

You may not have heard of Dave Daley, but a lot of writers know him as The Guy Who Can Get Writers To Do Anything. He's a freelance editor of sorts, and is responsible for the writing a story in twenty minutes thing, and the "Tag-Team" stories that ran a couple years back in the (White Plains, NY) Journal-News.

His latest project is a short-fiction-serialization project called Five Chapters. Every week he publishes a new story over five days. So far there have been a ton of contributors, including Thisbe Nissen, Vendela Vida, Aimee Bender, Jennifer Egan, and me. Everything's archived, in case you missed it.

So how does he work that magic on the scribblers of the world? By inventing challenges any writer worth his salt would feel like a fool for resisting. I wouldn't mind a literary scene populated by more inventive editors like Dave, who like to push writers out of their comfort zones--and I'm looking forward to receiving his next directive.

His latest project is a short-fiction-serialization project called Five Chapters. Every week he publishes a new story over five days. So far there have been a ton of contributors, including Thisbe Nissen, Vendela Vida, Aimee Bender, Jennifer Egan, and me. Everything's archived, in case you missed it.

So how does he work that magic on the scribblers of the world? By inventing challenges any writer worth his salt would feel like a fool for resisting. I wouldn't mind a literary scene populated by more inventive editors like Dave, who like to push writers out of their comfort zones--and I'm looking forward to receiving his next directive.

Monday, January 29, 2007

A Great First Paragraph

I hope a few of you are fans of the late Stanley Elkin, whose antic and erudite comic novels inspired me enormously when my writing career was getting started. Elkin is one of those writers whose unevenness obscures his brilliance--on the sentence level, the paragraph level, the chapter level even, he's without peer. But his books rarely come fully together, at least for me.

There are a couple of perfect ones though, most notably The Magic Kingdom, which is about a group of terminally ill children on a trip to Disneyland. It's one of the funniest books I've ever read. And no, I'm not kidding.

Anyway, I often start my semester of teaching by asking students to bring in their favorite opening sentences and paragraphs. Most people bring in great books that happen to have great openings--I always try to bring in flawed books. A standby in this department is Elkin's The Franchiser. Of course there are people smarter than I am (William Gass, for instance, see link) who think it's perfect all the way through, but never mind. Here's the opening:

You could put three hundred pages of Christopher Hitchens behind that, and I'd still buy it.

There are a couple of perfect ones though, most notably The Magic Kingdom, which is about a group of terminally ill children on a trip to Disneyland. It's one of the funniest books I've ever read. And no, I'm not kidding.

Anyway, I often start my semester of teaching by asking students to bring in their favorite opening sentences and paragraphs. Most people bring in great books that happen to have great openings--I always try to bring in flawed books. A standby in this department is Elkin's The Franchiser. Of course there are people smarter than I am (William Gass, for instance, see link) who think it's perfect all the way through, but never mind. Here's the opening:

Past the orange roof and turquoise tower, past the immense sunburst of the green and yellow sign, past the golden arches, beyond the low buff building, beside the discrete hut, the dark top hat on the studio window shade, beneath the red and white longitudes of the enormous bucket, coming up to the thick shaft of the yellow arrow piercing the royal-blue field, he feels he is at home. Is it Nashville? Elmira, New York? St. Louis County? A Florida key? The Illinois arrowhead? Indiana like a holster, Ohio like a badge? Is he north? St. Paul, Minn.? Northeast? Boston, Mass.? The other side of America? Salt Lake? Los Angeles? At the bottom of the country? The Texas udder? Where? In Colorado's frame? Wyoming like a postage stamp? Michigan like a mitten? The chipped, eroding bays of the Northwest? Seattle? Bellingham, Washington?

Somewhere in the packed masonry of states.

You could put three hundred pages of Christopher Hitchens behind that, and I'd still buy it.

Sunday, January 28, 2007

Serial Memoirs

I'll read pretty much any memoir, because I find it interesting to see how people take the raw and meaningless material of their lives and slap into narrative shape. However, I think we should call a moratorium on serial memoirizing. Too often a writer puts out a really excellent, juicy memoir (like Kathryn Harrison's The Kiss, which is about her affair with her father (!)), and then, once she's established herself as a memoirist, follows it up with one or more lesser books that cover very similar ground (Harrison's The Mother Knot). These follow-up memoirs tend to toss together lots of unrelated material in a fragmented fashion, and almost always include therapy scenes, in which we are forced to watch the writer healing from the traumas of the other books. Okay, I'm banning therapy scenes, too.

How about this: from now on everyone (even those of us with nice parents and no drug problems) gets exactly one memoir. After that, you have to move on to other people.

How about this: from now on everyone (even those of us with nice parents and no drug problems) gets exactly one memoir. After that, you have to move on to other people.

Saturday, January 27, 2007

Poems-For-All

We just added a new link to our link list down there on the left: a project called Poems-For-All, in Sacramento, California. It came to our attention via friend and W6 reader Zoe Venditozzi, who will be publishing a poem with them soon. From their "about" page:

We just added a new link to our link list down there on the left: a project called Poems-For-All, in Sacramento, California. It came to our attention via friend and W6 reader Zoe Venditozzi, who will be publishing a poem with them soon. From their "about" page:They're scattered around town — on buses, trains, cabs, in restrooms, bars, left along with the tip; stuffed into a stranger's back pocket. Whatever. Wherever. Small poems in small booklets half the size of a business card. A project of the 24th street irregular press, which cranks them out to be taken by the handful and scattered like seeds by those who want to see poetry grow in a barren cultural landscape.

Hot diggity, I like the sound of that. Rhian's the kind of person who will stop and pick up every piece of printed refuse she sees, in the hope that it will contain something good. It hardly ever does. Projects like these can bring a little balance to the vast meaningless logorrhea of the world--let's hear it for guerilla publishing.

Friday, January 26, 2007

Underrated Fiction: The World As I Found It

Bruce Duffy published The World As I Found It in 1987 and I first read it a few years after, having come across a copy in a bookstore in Ireland, I think. Reading the book was one of those rare transforming experiences that made me realize I wanted nothing out of life except to do that. It's the kind of book that is so good, you fall in love with the font (Bembo) and think all books should be printed in it.

It's a 700-page novel about Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell, but it's somehow funny, humane, and exciting, as well as brainy. Perhaps the book isn't more well-known because the subject matter puts people off, or maybe the publisher just didn't print enough copies for it to gather the cult following it deserves. I've always felt bad about it, because it took Duffy ten years to write (according to the flap copy; I've never met the guy though I certainly owe him a fan letter) and it's clearly a life's work.

It's a 700-page novel about Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell, but it's somehow funny, humane, and exciting, as well as brainy. Perhaps the book isn't more well-known because the subject matter puts people off, or maybe the publisher just didn't print enough copies for it to gather the cult following it deserves. I've always felt bad about it, because it took Duffy ten years to write (according to the flap copy; I've never met the guy though I certainly owe him a fan letter) and it's clearly a life's work.

Listen to Fred Seidel

I posted earlier this month about Frederick Seidel's new book of poems, Ooga Booga, which Rhian had gotten me for Christmas...I just found out that the book has a website, and the website features audio of Seidel reading the poems. Check it out here.

I should add that my friend Dave Brenneman, a recording engineer, was the one who taped Seidel's readings, which is how I heard about it...

I should add that my friend Dave Brenneman, a recording engineer, was the one who taped Seidel's readings, which is how I heard about it...

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

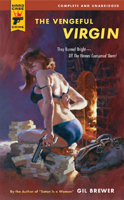

Hard Case Crime

So is anybody else digging the Hard Case Crime series? This is a new-ish crime fiction imprint that puts out a book every month; you can arrange to have a standing order charged to your credit card, and you'll just get the new book in the mail. The books look and feel fantastic--mass market paperbacks, just the right size, the title and author printed in bold sans serif type in yellow and black on a white spine, and an outrageously lurid fifties-retro painting on the cover.

So is anybody else digging the Hard Case Crime series? This is a new-ish crime fiction imprint that puts out a book every month; you can arrange to have a standing order charged to your credit card, and you'll just get the new book in the mail. The books look and feel fantastic--mass market paperbacks, just the right size, the title and author printed in bold sans serif type in yellow and black on a white spine, and an outrageously lurid fifties-retro painting on the cover.Some of the books are new; most are reissues. There are a few surprises--a Stephen King novella, a reprint of Madison Smartt Bell's Straight Cut, which is hardly what you'd call hard-boiled. And honestly, some of the books are kind of bad. It hardly matters, though. There are enough gems to keep you excited for the next one to show up, and the entire operation feels like a throwback to a bygone era--not just the books themselves, but the idea of getting them in the mail, direct from the publisher.

If you'd like to read a book written by a woman, by the way, forget it. So far there are precisely zero. If, however, you like the idea of getting shot in the head by one, especially a totally hot one in her underwear, then you're in business.

On a related note, there's a part of me that wishes everything were a mass market paperback. I'd happily pay a little extra for nice, acid-free paper, but I don't enjoy paying for hard covers and rough-cut pages--and I especially don't enjoy thinking of all the people who don't bother buying my own stuff when it comes out because it costs twenty-five dollars. I wish every decent book cost ten bucks. I wish every decent book could fit in your jeans pocket.

End of rant.

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

The Seven Basic Plots

I found something interesting at my bookstore's big blow-out sale: Christopher Booker's The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. At 700 pages it's a bit much to sit down and read front to back, at least for me, at least at the moment. But in skimming through I happened upon an interesting idea: DNA, Booker says, is nature's way of providing us with blueprints for physical development, and storytelling gives us our blueprints for psychological and social development.

I can buy that. In fact, I buy it a lot more readily than I do some other lit-critty ways of looking at literature. It helps explain some of my ambivalence over morality and literature: on the one hand, I'm disturbed by immoral novels, or more often movies, in which, for example, violence is glorified. On the other I reject the idea that a work of art needs to have a strong and easily identifiable moral.

If a story is a kind of guidebook for human growth, it makes sense that morality is a vital component. But as human society has become so incredibly complex, stories with simple morals make lousy guidebooks.

I hope Booker doesn't make the case that genre fiction, because it adheres so closely to ancient storytelling archetypes, is somehow better and more pure than literary fiction (which, hm, has become its own genre lately, anyway).

I can buy that. In fact, I buy it a lot more readily than I do some other lit-critty ways of looking at literature. It helps explain some of my ambivalence over morality and literature: on the one hand, I'm disturbed by immoral novels, or more often movies, in which, for example, violence is glorified. On the other I reject the idea that a work of art needs to have a strong and easily identifiable moral.

If a story is a kind of guidebook for human growth, it makes sense that morality is a vital component. But as human society has become so incredibly complex, stories with simple morals make lousy guidebooks.

I hope Booker doesn't make the case that genre fiction, because it adheres so closely to ancient storytelling archetypes, is somehow better and more pure than literary fiction (which, hm, has become its own genre lately, anyway).

Monday, January 22, 2007

Beatles Books

Rhian can attest to my inexplicable and undying affection for rock and roll documentaries--I've made her sit through about half a dozen. It's not the music that gets me--though I often like it--but the spectacle of (usually) four (always) arrogant (traditionally) men, desperately trying to get along with one another for years on end. As a portrait of group creativity and its pitfalls, these movies are instructive indeed.

It's amazing the Beatles lasted as long as they did, but because they did, we can spend our entire lives reading books about them, if we wish. Two recent ones are standouts, though--Geoff Emerick's Here, There, and Everywhere, and Recording the Beatles, by Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew.

The former is an as-told-to memoir by the head engineer on the late Beatles sessions; Emerick started in at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road) when he was 16, and found himself behind the mixing board, recording Revolver, before he was out of his teens. Emerick is responsible for a lot of the now commonplace, but then highly innovative, sound experiments that characterize the last few Beatles records; he invented many of the effects recording musicians take for granted today. The book is a very fast read--it's told in a direct, engaging style, and is packed with entertaining anecdotes. Emerick comes off as a regular bloke who happens to be brilliant at one specific thing, and it's this thing that makes him a witness to, and maker of, musical history. He doesn't have a lot of tolerance for moodiness--he loves Paul and never cared much for George--but he's otherwise a pleasure to be with for a few hundred pages.

The latter book, Recording the Beatles, is for geeks only. It explains, in exhaustive detail, every piece of equipment used on every Beatles recording, and offers up some major eye candy as well, in the form of glorious photographs, diagrams, and maps. The book is superbly written, is perhaps the best book about recording music, ever. Most surprising is the authors' meticulous examination of the culture of EMI--the heirarchy of its employees, what rules were broken (often by Emerick), and why. It's a unique portrait of a particular time and place.

Even as a physical artifact, Recording the Beatles is an amazing achievement--it's enormous, printed on heavy stock, and comes in a clever cardboard slipcase that mimics the boxes that used to house EMI's analog tape. It'll also run you a benjamin and, if you prop it open on your lap for more than an hour, you'll soon be writing checks to your urologist. It's worth it, though, if you're as big a dork as I am.

It's amazing the Beatles lasted as long as they did, but because they did, we can spend our entire lives reading books about them, if we wish. Two recent ones are standouts, though--Geoff Emerick's Here, There, and Everywhere, and Recording the Beatles, by Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew.

The former is an as-told-to memoir by the head engineer on the late Beatles sessions; Emerick started in at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road) when he was 16, and found himself behind the mixing board, recording Revolver, before he was out of his teens. Emerick is responsible for a lot of the now commonplace, but then highly innovative, sound experiments that characterize the last few Beatles records; he invented many of the effects recording musicians take for granted today. The book is a very fast read--it's told in a direct, engaging style, and is packed with entertaining anecdotes. Emerick comes off as a regular bloke who happens to be brilliant at one specific thing, and it's this thing that makes him a witness to, and maker of, musical history. He doesn't have a lot of tolerance for moodiness--he loves Paul and never cared much for George--but he's otherwise a pleasure to be with for a few hundred pages.

The latter book, Recording the Beatles, is for geeks only. It explains, in exhaustive detail, every piece of equipment used on every Beatles recording, and offers up some major eye candy as well, in the form of glorious photographs, diagrams, and maps. The book is superbly written, is perhaps the best book about recording music, ever. Most surprising is the authors' meticulous examination of the culture of EMI--the heirarchy of its employees, what rules were broken (often by Emerick), and why. It's a unique portrait of a particular time and place.

Even as a physical artifact, Recording the Beatles is an amazing achievement--it's enormous, printed on heavy stock, and comes in a clever cardboard slipcase that mimics the boxes that used to house EMI's analog tape. It'll also run you a benjamin and, if you prop it open on your lap for more than an hour, you'll soon be writing checks to your urologist. It's worth it, though, if you're as big a dork as I am.

Sunday, January 21, 2007

I Can't Believe I Read the Whole Thing

I confess I'm a terrible literature snob. Normally I wouldn't touch a book with a skinny cartoon woman in high heels on the cover. Or a pink book, or a book with lots of brand names in it. But somehow I found myself caught up in The Devil Wears Prada this weekend. And for the first third, it was fun and energetic; its giddy bitchiness it reminded me a little of The Valley of the Dolls (which I love, though its charm largely defies explanation). But the middle third repeated the same scenes over and over ("Andrea! Where's my latte?" she screamed. "Right here, Miranda," I answered, tottering in on my Jimmy Choos.") The final third was tedious and exasperating, though thankfully easy to skim.

I confess I'm a terrible literature snob. Normally I wouldn't touch a book with a skinny cartoon woman in high heels on the cover. Or a pink book, or a book with lots of brand names in it. But somehow I found myself caught up in The Devil Wears Prada this weekend. And for the first third, it was fun and energetic; its giddy bitchiness it reminded me a little of The Valley of the Dolls (which I love, though its charm largely defies explanation). But the middle third repeated the same scenes over and over ("Andrea! Where's my latte?" she screamed. "Right here, Miranda," I answered, tottering in on my Jimmy Choos.") The final third was tedious and exasperating, though thankfully easy to skim.One of the great things about The Valley of the Dolls is the way all the characters end up dead, crazy, or addicted to drugs. If their shallowness and vanity bug you in the previous 400 pages, it's deeply satisfying to see them punished in the end. No such pleasure in The Devil Wears Prada, where everyone ends up happy and content.

It's not that I don't like happy endings; I just hate that they've become de rigeur, at least for books aimed at women. Could Jacqueline Susann have gotten away with her decidedly dark finish if she'd written the book in 2006 instead of 1966? I doubt it. And I doubt the 1966 audience would have much patience for the fairy-tale endings we seem obsessed with.

Saturday, January 20, 2007

Character, Character, Character

That's the writerly equivalent of the realtor's mantra--it's taken on faith that everything, in literary fiction, is subservient to character. I've never quite bought it--I like plot, and talk about it often when I teach writing classes. At a weekend seminar on novel writing at a college, I once suggested that students might want to outline the plot of their novel. I was met with stunned silence. "We're not supposed to talk about plot," someone actually said.

But you know what? It's true. Everything is subservient to character. Even in popular fiction. Especially popular ficiton. I just read the new Richard Stark, Ask The Parrot. In it, Stark/Westlake's criminal protagonist, Parker, gets involved in a heist at a racetrack, and of course everything goes wrong. At first glance, the book is all plot, delivered in the unadorned, supremely efficient Stark prose--a manhunt, a car chase, a shootout. But nothing that happens happens for no reason. It all happens because of who people are--the nosy granddaughter, the paranoid mechanic, the guilty father, the disgruntled employee. Stark's brush is broad, his characters tend to fall into types, but there is no question, they are running the show. They make things happen--specific things--because of who they are.

This is why I'll choose skillful noir over bloated lyricism any day--character beats language, hands down. I think the reason I was so jazzed up over the Zadie Smith the other day is that, like Stark, she actually notices people, and makes them act out their desires. Of course Smith's got the chops in other areas, too--all of them, really. Think of the Stark book as the best after-dinner mint you ever had.

But you know what? It's true. Everything is subservient to character. Even in popular fiction. Especially popular ficiton. I just read the new Richard Stark, Ask The Parrot. In it, Stark/Westlake's criminal protagonist, Parker, gets involved in a heist at a racetrack, and of course everything goes wrong. At first glance, the book is all plot, delivered in the unadorned, supremely efficient Stark prose--a manhunt, a car chase, a shootout. But nothing that happens happens for no reason. It all happens because of who people are--the nosy granddaughter, the paranoid mechanic, the guilty father, the disgruntled employee. Stark's brush is broad, his characters tend to fall into types, but there is no question, they are running the show. They make things happen--specific things--because of who they are.

This is why I'll choose skillful noir over bloated lyricism any day--character beats language, hands down. I think the reason I was so jazzed up over the Zadie Smith the other day is that, like Stark, she actually notices people, and makes them act out their desires. Of course Smith's got the chops in other areas, too--all of them, really. Think of the Stark book as the best after-dinner mint you ever had.

Labels:

characters,

donald westlake,

noir,

plot,

richard stark

Friday, January 19, 2007

One More Time About On Beauty

I should add that I finished On Beauty myself last night--it's terrific. Why on earth didn't I read Zadie Smith before? What an idiot. I felt very much at home in this book, with its painfully acute observation of character, its antic prose style, its over-the-top confrontations and juxtapositions...it's the kind of thing I write, except, like, better. Perhaps Rhian is an Impeccable Arbiter of Literary Taste after all.

Mark Strand's Man and Camel

I just read Mark Strand's new collection of poems, Man and Camel. It's a good collection, perhaps a little lopsided, with the stronger poems near the front.

I think Strand is at his best when he's dealing with the tangibly strange--the poems that draw you in like a story, then lead you to unexpected places. "A man leaves for the next town to pick up a cake," goes the first line of "Cake." "People Walking Through the Night" begins, "They carried what they had in garbage bags and knapsacks." Strand has written fiction (peculiar fiction) and understands suspense--he's like a guy walking toward you with a birthday present poorly concealed behind his back. His poems like to pretend to be simple.

My favorite of the bunch is "Storm." "On the night of our house arrest / a howling wind tore through the streets," it begins, and ends with the narrator fleeing his home:

You can almost make yourself miss that "as if"...but not quite.

I think Strand is at his best when he's dealing with the tangibly strange--the poems that draw you in like a story, then lead you to unexpected places. "A man leaves for the next town to pick up a cake," goes the first line of "Cake." "People Walking Through the Night" begins, "They carried what they had in garbage bags and knapsacks." Strand has written fiction (peculiar fiction) and understands suspense--he's like a guy walking toward you with a birthday present poorly concealed behind his back. His poems like to pretend to be simple.

My favorite of the bunch is "Storm." "On the night of our house arrest / a howling wind tore through the streets," it begins, and ends with the narrator fleeing his home:

I ran downstairs and called

for my horse. "To the sea," I whispered, and off

we went and how quick we were, my horse and I,

riding over the fresh green fields, as if to our freedom.

You can almost make yourself miss that "as if"...but not quite.

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Likeable Characters

Something I was reading the other day quoted Claire Messud as saying (and I have to paraphrase, because I don't remember where I saw this and Google is not being helpful) that she doesn't believe in making characters appealing, because real people are unappealing -- we just tend to hide our less pleasant characteristics.

That's been rolling around in my head for days now. I'm not sure I agree -- I find plenty of people appealing, even people I know pretty well -- but then again, I object to the idea that a character has to be someone you'd want for a close friend. (Similarly, I don't think a good president is necessarily someone you'd want to have a beer with.) Hans Castorp is quite a sad sack whiny pants, but that makes the ending of The Magic Mountain all the more shocking and moving.

But I do think that the writer has to like his characters -- flaws and all. (And I'm talking about main characters in literary fiction -- not thrillers!) When an author despises or looks down on his characters, it leaves pretty much no opportunity for the reader to connect with them. And a good writer, I think, ought to be able to make the most horrible characters perversely appealing.

That's been rolling around in my head for days now. I'm not sure I agree -- I find plenty of people appealing, even people I know pretty well -- but then again, I object to the idea that a character has to be someone you'd want for a close friend. (Similarly, I don't think a good president is necessarily someone you'd want to have a beer with.) Hans Castorp is quite a sad sack whiny pants, but that makes the ending of The Magic Mountain all the more shocking and moving.

But I do think that the writer has to like his characters -- flaws and all. (And I'm talking about main characters in literary fiction -- not thrillers!) When an author despises or looks down on his characters, it leaves pretty much no opportunity for the reader to connect with them. And a good writer, I think, ought to be able to make the most horrible characters perversely appealing.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

By the Way...

...Rhian just poked her head over my shoulder to remind me that, on the Julian Calendar anyway, it's the birthday of Anton Chekhov, the man who named this blog. Raise a glass to the good doctor, if you will.

Where's All the Good Science Fiction?

I have a half-baked theory about genre fiction--that, on the whole, it serves a propagandistic purpose. Crime novels are about social problems, romances are about wish fulfillment, westerns are about politics. Science fiction has its roots, I think, in our ambivalence about science, and the ways it can be used as a force for good or evil; it's always been forward-looking, has always tried to tackle problems that don't yet exist.

As such, its aims have always been admirable (the right-wing screeds of Michael Crichton notwithstanding). But often, the things that make books great are missing in science fiction. Characters too often stand for things other than themselves, and so the exploration of consciousness--of what it means to be human--gets short shrift.

A few writers have tried to go against the grain, though. Octavia Butler springs to mind; so does Ursula LeGuin, whose The Left Hand of Darkness reinvented gender in order to probe human nature in new ways. And Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars Trilogy explored, among other things, what living for 200 years would do to a person's mind.

Lately though I've really been into China Mieville, whose trilogy of novels set in his invented world of Bas Lag somehow manage to bundle all that is good about SF with almost everything that's good about literary fiction--his characters think deeply, in a deeply strange place. You could accuse him of overwriting (I do anyway), but the exhaustiveness of his imagination almost requires it. There's just so damned much to say. The best of these books is probably The Scar, which is about an embittered linguist on a transcontinental sea voyage that is interrupted by pirates, who steal the ship she's on and add it to their thousand-year-old floating continent of booty. The story takes place in the equivalent of earth's mid-ninteenth century, but instead of one sentient species, there are dozens. There is science, but there is also magic. There is oil to be drilled for--but there's also something called "rockmilk." There is slavery, but the slaves are, more often than not, genetically-engineered mutants or man-machine hybrids. And all this makes perfect sense, and does not seem remotely silly.

I wish more people with Mieville's chops would apply it to science fiction--I think there's a lot more to be done there than many writers have bothered to do. I've been on my own case for years, actually, to write a science fiction novel, and one of these days I'll do it. But I tried it once, and man, it was really freaking hard. I dropped it after forty pages and did something else.

Maybe what it takes is to be superhuman--maybe you've got to be science fiction to write it.

As such, its aims have always been admirable (the right-wing screeds of Michael Crichton notwithstanding). But often, the things that make books great are missing in science fiction. Characters too often stand for things other than themselves, and so the exploration of consciousness--of what it means to be human--gets short shrift.

A few writers have tried to go against the grain, though. Octavia Butler springs to mind; so does Ursula LeGuin, whose The Left Hand of Darkness reinvented gender in order to probe human nature in new ways. And Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars Trilogy explored, among other things, what living for 200 years would do to a person's mind.

Lately though I've really been into China Mieville, whose trilogy of novels set in his invented world of Bas Lag somehow manage to bundle all that is good about SF with almost everything that's good about literary fiction--his characters think deeply, in a deeply strange place. You could accuse him of overwriting (I do anyway), but the exhaustiveness of his imagination almost requires it. There's just so damned much to say. The best of these books is probably The Scar, which is about an embittered linguist on a transcontinental sea voyage that is interrupted by pirates, who steal the ship she's on and add it to their thousand-year-old floating continent of booty. The story takes place in the equivalent of earth's mid-ninteenth century, but instead of one sentient species, there are dozens. There is science, but there is also magic. There is oil to be drilled for--but there's also something called "rockmilk." There is slavery, but the slaves are, more often than not, genetically-engineered mutants or man-machine hybrids. And all this makes perfect sense, and does not seem remotely silly.

I wish more people with Mieville's chops would apply it to science fiction--I think there's a lot more to be done there than many writers have bothered to do. I've been on my own case for years, actually, to write a science fiction novel, and one of these days I'll do it. But I tried it once, and man, it was really freaking hard. I dropped it after forty pages and did something else.

Maybe what it takes is to be superhuman--maybe you've got to be science fiction to write it.

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

What Rhian's Not Mentioning About Alice Munro

My wife, in her last post, didn't mention that we have Alice Munro's new book sitting on the coffee table, where it's been sitting for weeks, unread.

Why are we avoiding our favorite living writer? Because the stories in this new book are autobiographical. Alice Munro says so, right there in the introduction. If we open it up, we may find out the truth. And nothing's scarier than that.

Why are we avoiding our favorite living writer? Because the stories in this new book are autobiographical. Alice Munro says so, right there in the introduction. If we open it up, we may find out the truth. And nothing's scarier than that.

Alice Munro and Real Life

I first read Alice Munro in college, when a friend pressed Lives of Girls and Women on me, saying that I would relate to it. She was right. I loved that book not because I admired it, but because Munro said things about my life at that moment that I hadn't even noticed before. My own life felt larger and more rich because of her life.

But it's not her life -- it's fiction, right? I'd always assumed that there's a strong autobiographical source for much of AM's fiction, if for no other reason than the recurrence of certain motifs: the inappropriate lover, the sick mother, the bourgeois husband. And one other that I might not have noticed if it weren't for the latest story in Harper's: drowning.

"Miles City, Montana" is the big drowning story, with one drowned child in the back story and an near-drowning in the front. There's one in an old story, "Walking on Water," and a sunk car with people in it in a later story. I think there are more. Anyway, enough to make a person wonder, "So... what is it with Alice Munro and drowning?"

You wouldn't ask that of a memoirist -- she would tell you right out, and that would be that. One of the reasons I prefer fiction to memoir is because fiction lets the writer work through variations on a theme. In one story the protagonist is just a witness to a drowning; in another story she's at fault through neglect; in another she's completely to blame.

What really happened? Munro would probably say it doesn't matter, and I guess it doesn't. Knowing wouldn't make me get more out of the stories, or cause me to like them less. Still, wondering about her real life has always been a part of my experience reading AM -- thinking about how what really happened gets turned around and comes out as fiction is endlessly fascinating.

But it's not her life -- it's fiction, right? I'd always assumed that there's a strong autobiographical source for much of AM's fiction, if for no other reason than the recurrence of certain motifs: the inappropriate lover, the sick mother, the bourgeois husband. And one other that I might not have noticed if it weren't for the latest story in Harper's: drowning.

"Miles City, Montana" is the big drowning story, with one drowned child in the back story and an near-drowning in the front. There's one in an old story, "Walking on Water," and a sunk car with people in it in a later story. I think there are more. Anyway, enough to make a person wonder, "So... what is it with Alice Munro and drowning?"

You wouldn't ask that of a memoirist -- she would tell you right out, and that would be that. One of the reasons I prefer fiction to memoir is because fiction lets the writer work through variations on a theme. In one story the protagonist is just a witness to a drowning; in another story she's at fault through neglect; in another she's completely to blame.

What really happened? Munro would probably say it doesn't matter, and I guess it doesn't. Knowing wouldn't make me get more out of the stories, or cause me to like them less. Still, wondering about her real life has always been a part of my experience reading AM -- thinking about how what really happened gets turned around and comes out as fiction is endlessly fascinating.

Monday, January 15, 2007

The Detective as a Purifying Force

I'm about halfway through this new-ish translation of Crime and Punishment I posted about a couple of days ago, and came to the bit in the middle where Porfiry, the investigator, shows up. I'd forgotten how surprising this scene is--Raskolnikov and his friend Razumikhin go to Porfiry's apartment in order for Raskolnikov to see if he can recover the items he pawned with the murdered pawnbroker (murdered, of course, by Raskolnikov himself). And after telling Raskolnikov that he can indeed recover the items, Porfiry says:

And a few moments later, he adds, "You are the only one"--that is, of the pawners--"who has not been so good as to pay us a visit."

The overall impression, which both Raskolnikov and the reader takes away from this conversation, is that Porfiry already knows Raskolnikov is the killer, and thus that his role is not to investigate the crime, but to serve as confessor to the criminal. He is the vessel into which the truth is supposed to be poured.

In a sense, every great literary detective is like this. The detective exists to receive the truth, and to know its implications. The possibility that this is so seems to mesmerize Raskolnikov--indeed, he keeps thinking Porfiry is winking at him, but is never entirely sure if this impression is real. The scene recasts Raskolnikov's supposed madness as a kind of spiritual dissonance, a moral imbalance. One thinks of President Bush's deer-in-the-headlights stare during his speech the other night, the gaze of a lunatic being dragged from his bunker into the light of day.

"Your things would not be lost in any event," he went on calmly and coldly, "because I've been sitting here a long time waiting for you."

And a few moments later, he adds, "You are the only one"--that is, of the pawners--"who has not been so good as to pay us a visit."

The overall impression, which both Raskolnikov and the reader takes away from this conversation, is that Porfiry already knows Raskolnikov is the killer, and thus that his role is not to investigate the crime, but to serve as confessor to the criminal. He is the vessel into which the truth is supposed to be poured.

In a sense, every great literary detective is like this. The detective exists to receive the truth, and to know its implications. The possibility that this is so seems to mesmerize Raskolnikov--indeed, he keeps thinking Porfiry is winking at him, but is never entirely sure if this impression is real. The scene recasts Raskolnikov's supposed madness as a kind of spiritual dissonance, a moral imbalance. One thinks of President Bush's deer-in-the-headlights stare during his speech the other night, the gaze of a lunatic being dragged from his bunker into the light of day.

Sunday, January 14, 2007

More On On Beauty

While thinking about my last blog post and feeling weird about the broad conclusions I implied (that RME is an Impeccable Arbiter of Literary Taste and the people responsible for Amazon ratings are dumb) it occurred to me exactly what an Amazon rating is: an indicator of just how closely a book hews to the reader's expectations for it. The cozy mystery earned its five stars because it is flawlessly cozy, while On Beauty was read by people who'd had widely varying ideas about what they were getting into. It's a strange, idiosyncratic novel that, to me, was so much fun in part because of the way it upended my expectations. Of course, there's a reason "idiosyncratic" isn't much used as a marketing term.

Which, incidentally, explains the popularity of McDonald's, too: if nothing else, it is at least always perfectly McDonald'sy.

Though I have been careful to avoid reading Amazon reviews of my own book, I did once stumble upon a negative review that said my book sucked because "it wasn't even scary." That's pretty easy criticism to accept, since I hadn't tried to make it scary. If only all criticism were like that.

Which, incidentally, explains the popularity of McDonald's, too: if nothing else, it is at least always perfectly McDonald'sy.

Though I have been careful to avoid reading Amazon reviews of my own book, I did once stumble upon a negative review that said my book sucked because "it wasn't even scary." That's pretty easy criticism to accept, since I hadn't tried to make it scary. If only all criticism were like that.

More on Translations

In the comments of my last post, reader 5 red brought up one of my favorite writers:

I've often wondered the same thing about other writers, but I don't worry too much about it in Haruki Murakami's case. The reason is that he's a very rare beast among writers who don't ordinarily write in English: he is both 1) completely fluent in English, and 2) popular enough so that all his books are translated into English during his lifetime. He also has a couple of translators he knows well and whom he can work with...thus, his translations have a certain "official" status, at least in my mind, as he gets to vet them, and can actually appreciate the way they "feel" in English.

I wish I could remember where I found this, but I remember reading a short essay or interview with Murakami in which discussed his English translations and his feelings toward them. If I remember right, he liked them, but appreciated that they had a different flavor. If anyone knows what I'm talking about, let us know.

On a side note, I got a real laugh when flipping through the Spanish edition of one of my own books...in the English, the character refers to someone having real "cojones," and in the translation there's a footnote reading, "In Spanish in the original."

This talk of translation also brings to the fore the nagging question I have when I read Murakami's work. I can't help wondering what his work is like in Japanese. I've convinced myself that it's even better, and I feel like I'm missing out.

I've often wondered the same thing about other writers, but I don't worry too much about it in Haruki Murakami's case. The reason is that he's a very rare beast among writers who don't ordinarily write in English: he is both 1) completely fluent in English, and 2) popular enough so that all his books are translated into English during his lifetime. He also has a couple of translators he knows well and whom he can work with...thus, his translations have a certain "official" status, at least in my mind, as he gets to vet them, and can actually appreciate the way they "feel" in English.

I wish I could remember where I found this, but I remember reading a short essay or interview with Murakami in which discussed his English translations and his feelings toward them. If I remember right, he liked them, but appreciated that they had a different flavor. If anyone knows what I'm talking about, let us know.

On a side note, I got a real laugh when flipping through the Spanish edition of one of my own books...in the English, the character refers to someone having real "cojones," and in the translation there's a footnote reading, "In Spanish in the original."

Saturday, January 13, 2007

Zadie Smith's On Beauty... and Amazon

I just finished On Beauty and have to say I loved every page of it. I kept looking up from the book as I was reading to tell JRL about something I thought was particularly great. But this afternoon, when I was thinking about blogging about the book, I decided to check out what Amazon had to say about it. YIPES! On Beauty gets a mere three stars out five, considerably less than the typical four to four-and-a-half out of five. Even the book that currently qualifies as The Worst Book I Ever Read (a "cozy" mystery that shall remain nameless) gets a full five.

Why? I was staggered by Smith's ability to fully inhabit so many different characters so convincingly. She can snap a scene into full color with just a sentence or two -- she has a faultless ear for the way people speak and an eye for the detail that makes everything real. Her depiction of a teenager working at a Virgin record store was perfect -- I don't need to get a job there now; I know what it's like. And a scene between a middle-aged Englishman and his elderly father was just as spot-on.

What? Did you say something about plot? Oh, yeah. Well, there was an affair. Hmm... let's see... Okay, so there's not much in the way of a conventional plot. But did I miss it? No, actually; I didn't even notice until I read the Amazon reviews. The constantly shifting relationships between the characters kept me riveted. Zadie Smith is very, very smart (I don't even want to think about how much younger than me she is) and it was just a pleasure to spend some time in her mind.

I don't know whether to despair at the book's relatively low Amazon rating or to just shrug my shoulders -- after all, according to the tenets of popularity McDonald's is a great restaurant, and anyway, it's not like On Beauty didn't win about 9,000 awards.

But won't that low score prevent some people from buying the book? It will, and that's a shame.

Why? I was staggered by Smith's ability to fully inhabit so many different characters so convincingly. She can snap a scene into full color with just a sentence or two -- she has a faultless ear for the way people speak and an eye for the detail that makes everything real. Her depiction of a teenager working at a Virgin record store was perfect -- I don't need to get a job there now; I know what it's like. And a scene between a middle-aged Englishman and his elderly father was just as spot-on.

What? Did you say something about plot? Oh, yeah. Well, there was an affair. Hmm... let's see... Okay, so there's not much in the way of a conventional plot. But did I miss it? No, actually; I didn't even notice until I read the Amazon reviews. The constantly shifting relationships between the characters kept me riveted. Zadie Smith is very, very smart (I don't even want to think about how much younger than me she is) and it was just a pleasure to spend some time in her mind.

I don't know whether to despair at the book's relatively low Amazon rating or to just shrug my shoulders -- after all, according to the tenets of popularity McDonald's is a great restaurant, and anyway, it's not like On Beauty didn't win about 9,000 awards.

But won't that low score prevent some people from buying the book? It will, and that's a shame.

Friday, January 12, 2007

United Pants of America

I'm re-reading Crime and Punishment right now, but this time I'm trying a new translation with a reading group I'm in--the one by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, whose Brothers Karamazov is so superb. I originally read this book in the David Magarshack translation, and this is the edition that made it my favorite novel. But I have to admit--though Magarshack still rules the roost when it comes to Chekhov, this Vintage C&P is the new king.

How come? Take a look at this passage, from the Magarshack version. Here, Raskolnikov's friend Razumikhin has brought him some new clothes. He fits a new cap on Raskolnikov's head, and then:

All right, then...fair enough, if a little puzzling. Now read the Pevear/Volokhonsky:

Now, you see the difference? The second one is freaking hilarious. And I greatly prefer the word "displayed" to Magarshack's "spread out"...the words are of equal utility, but the Vintage translation seems to emphasize the ridiculousness of the moment--as it's Raskolnikov's last thirty-five rubles, we learn, from which the pants money has been drawn.

I recommend either, of course, but if you're trying Dostoyevsky for the first time, go with the new one. It's very natural, nearly as good as the other great new translation I read recently, Lydia Davis's Swann's Way.

How come? Take a look at this passage, from the Magarshack version. Here, Raskolnikov's friend Razumikhin has brought him some new clothes. He fits a new cap on Raskolnikov's head, and then:

"Well, now, let's address ourselves to the United States of America, as we used to call it at school. A word of warning, though--I am proud of the trousers!" and he spread out before Raskolnikov a pair of grey summer trousers of light woolen material.

All right, then...fair enough, if a little puzzling. Now read the Pevear/Volokhonsky:

"Well, sir, now let's start on the United Pants of America, as we used to call them in school. I warn you, I'm proud of them," and he displayed before Raskolnikov a pair of gray trousers, made of lightweight summer wool.

Now, you see the difference? The second one is freaking hilarious. And I greatly prefer the word "displayed" to Magarshack's "spread out"...the words are of equal utility, but the Vintage translation seems to emphasize the ridiculousness of the moment--as it's Raskolnikov's last thirty-five rubles, we learn, from which the pants money has been drawn.

I recommend either, of course, but if you're trying Dostoyevsky for the first time, go with the new one. It's very natural, nearly as good as the other great new translation I read recently, Lydia Davis's Swann's Way.

Thursday, January 11, 2007

New Harper's

There's lots of interesting stuff in the February Harper's -- not the least of which is a story by Alice Munro. Whoa! I've been watching her stuff like a hawk since about 1989, and I don't think she's ever been in Harper's before. Does that mean the story was rejected by the New Yorker? They don't take everything of hers, nutty and depressing as that may seem (if they reject her, the rest of us might as well close up our lemonade stands and go home). I think I saw AM in the Atlantic, before they quit publishing fiction, and I read a marvelous something of hers in the Guardian magazine this summer.

But I'm saving that for later. Jonathan Lethem has an intriguing, if excessively clever, essay on plagiarism (it's plagiarized!) and Ian Jack, soon-to-be-ex-editor of Granta, asks why so many young novelists feel the need to thank page after page of people in the back of their books. (His idea is that writing has become a collaborative effort these days; I would argue instead that's it's all about a growing sense that publishing is a fancy cocktail party you should be grateful you got invited too -- and if you don't write your thank you notes, you can forget about another invitation.)

I also really enjoyed reading the Notebook (which used to be where Lewis Lapham posted his crazy/brilliant screeds) which is by Barbara Ehrenreich this month. Listening to her promote her new book on NPR, I thought she'd gone all soft (it's about "collective joy," which I don't doubt exists, but which I certainly can't vouch for) but no: she's as acerbic and smart as ever. The most recent NYT Magazine has an article on a new academic discipline: "Positive Psychology," which instead of focusing on problems and pathology, teaches students ways to be happy, like taking yoga and volunteering. Though I certainly don't want to knock volunteering (or yoga) I found the whole thing disturbing for reasons I couldn't quite put a finger on, but to my relief Ehrenreich does it for me.

The older I get, the more I admire bad-ass middle-aged ladies.

But I'm saving that for later. Jonathan Lethem has an intriguing, if excessively clever, essay on plagiarism (it's plagiarized!) and Ian Jack, soon-to-be-ex-editor of Granta, asks why so many young novelists feel the need to thank page after page of people in the back of their books. (His idea is that writing has become a collaborative effort these days; I would argue instead that's it's all about a growing sense that publishing is a fancy cocktail party you should be grateful you got invited too -- and if you don't write your thank you notes, you can forget about another invitation.)

I also really enjoyed reading the Notebook (which used to be where Lewis Lapham posted his crazy/brilliant screeds) which is by Barbara Ehrenreich this month. Listening to her promote her new book on NPR, I thought she'd gone all soft (it's about "collective joy," which I don't doubt exists, but which I certainly can't vouch for) but no: she's as acerbic and smart as ever. The most recent NYT Magazine has an article on a new academic discipline: "Positive Psychology," which instead of focusing on problems and pathology, teaches students ways to be happy, like taking yoga and volunteering. Though I certainly don't want to knock volunteering (or yoga) I found the whole thing disturbing for reasons I couldn't quite put a finger on, but to my relief Ehrenreich does it for me.

But what is truly sinister about the positivity cult is that it seems to reduce our tolerance of other people's suffering...If no one will listen to my problems, I won't listen to theirs: "no whining," as the popular bumper stickers and wall plaques warn. Thus the cult acquires a viral-like reproductive energy, creating an empathy deficit that pushes ever more people into a harsh insistence on positivity in others.

The older I get, the more I admire bad-ass middle-aged ladies.

Wednesday, January 10, 2007

Dialogue!

Oh, my. Part of my approach to this novel I'm writing has been to avoid my strengths--dialogue and flashbacks--in order to try and dig myself a new groove. The protagonist is an unreliable narrator who rarely mentions his past and is completely alone in a forest for most of the book.

But today he made a phone call and whoa, it was like I'd been swinging five bats in the on-deck circle. I will probably have to erase half of it, somewhere down the line, but it was quite a pleasant tumble off the wagon.

Tomorrow, as penance, I'll have him fall into a hole.

But today he made a phone call and whoa, it was like I'd been swinging five bats in the on-deck circle. I will probably have to erase half of it, somewhere down the line, but it was quite a pleasant tumble off the wagon.

Tomorrow, as penance, I'll have him fall into a hole.

Tuesday, January 9, 2007

Robert Wilson Tackles Terrorism

I'm a bit of a crime fiction fanatic, but the worst kind you can be: the kind who wants the writing to be awesome. I think I'm more disappointed by bad crime novels than by pretty much every other sort of bad novel, and more delighted by a good one than is perhaps healthy. A good police procedural can serve as a near-perfect metaphor for the process of creative inspiration; a bad one makes a mockery of discovery.

By and large I've gotten the most enjoyment out of Scandinavia, beginning with the Swedish husband-and-wife team of Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, who wrote what has to be the greatest detective series of all time, in the 1960's and 70's. Their ten-book run included the stunning The Laughing Policeman and the deeply interior and ultimately optimistic The Locked Room. And their successors, who include Henning Mankell, Karin Fossum, Ake Edwardsson, and Arnaldur Indridason, have also written a veritable library of absorbing mysteries.

But what I've most looked forward to lately has been whatever Robert Wilson has just published, particularly the books featuring Spanish police detective Javier Falcón. Wilson is British, and writes about everywhere but Britain; the Falcón books, set in Seville, are the most convincing, and the character the one, among Wilson's oeurve, with whom he seems most engaged. The new one, The Hidden Assassins, is probably my least favorite of the bunch, but it's still pretty good, and I recommend it.

In it, Falcón finds himself presiding over a bombing that appears to be the work of Islamic terrorists. The investigation, of course, reveals that the bombing isn't so straightforward as that. This is no surprise, of course--but what sets the novel apart is the way it demonstrates the deep complexity of terrorism itself, the multiplicity of its connections, the depth of its political opportunism, and the way it is enabled by those who benefit from its condemnation.

Throughout, we see how the bombing worms itself into the lives of Falcón's friends, family, and associates, and get to enjoy more of the smart, exhausted self-doubt that characterizes this most lachrymose of policemen. Wilson loves to use Falcón to turn the clichés of crime fiction inside out. Here, he knocks a dent in the storied power of intuition:

Nothing in this book seems remotely like laziness, though you could fault Wilson for his mountains of (admittedly fascinating) expository dialogue. Still, it's lovely not to have to throw a crime novel across the room, especially one as heavy as this one.

By and large I've gotten the most enjoyment out of Scandinavia, beginning with the Swedish husband-and-wife team of Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, who wrote what has to be the greatest detective series of all time, in the 1960's and 70's. Their ten-book run included the stunning The Laughing Policeman and the deeply interior and ultimately optimistic The Locked Room. And their successors, who include Henning Mankell, Karin Fossum, Ake Edwardsson, and Arnaldur Indridason, have also written a veritable library of absorbing mysteries.

But what I've most looked forward to lately has been whatever Robert Wilson has just published, particularly the books featuring Spanish police detective Javier Falcón. Wilson is British, and writes about everywhere but Britain; the Falcón books, set in Seville, are the most convincing, and the character the one, among Wilson's oeurve, with whom he seems most engaged. The new one, The Hidden Assassins, is probably my least favorite of the bunch, but it's still pretty good, and I recommend it.

In it, Falcón finds himself presiding over a bombing that appears to be the work of Islamic terrorists. The investigation, of course, reveals that the bombing isn't so straightforward as that. This is no surprise, of course--but what sets the novel apart is the way it demonstrates the deep complexity of terrorism itself, the multiplicity of its connections, the depth of its political opportunism, and the way it is enabled by those who benefit from its condemnation.

Throughout, we see how the bombing worms itself into the lives of Falcón's friends, family, and associates, and get to enjoy more of the smart, exhausted self-doubt that characterizes this most lachrymose of policemen. Wilson loves to use Falcón to turn the clichés of crime fiction inside out. Here, he knocks a dent in the storied power of intuition:

Falcón was surprised at himself. He'd been such a scientific investigator in the past, always keen to get his hands on autopsy reports and forensic evidence. Now he spent more time tuning in to his intuition. He tried to persuade himself that it was experience but sometimes it seemed like laziness.

Nothing in this book seems remotely like laziness, though you could fault Wilson for his mountains of (admittedly fascinating) expository dialogue. Still, it's lovely not to have to throw a crime novel across the room, especially one as heavy as this one.

Monday, January 8, 2007

Women Who ( ) Too Much

While working at the bookstore the other day I was intrigued by a book in the Women's Health section titled Eating, Drinking, Overthinking because it summed up my life so perfectly. However, it occurred to me to wonder why this book is aimed at women, since, actually, the men I know indulge in all three just as heartily as them women, if not more so. More men are overweight, more men are alcoholics, and while I'm not sure exactly what "overthinking" is, certainly men do it too, if the statistics on stalking reflect men's tendency to have obsessive thoughts.

While working at the bookstore the other day I was intrigued by a book in the Women's Health section titled Eating, Drinking, Overthinking because it summed up my life so perfectly. However, it occurred to me to wonder why this book is aimed at women, since, actually, the men I know indulge in all three just as heartily as them women, if not more so. More men are overweight, more men are alcoholics, and while I'm not sure exactly what "overthinking" is, certainly men do it too, if the statistics on stalking reflect men's tendency to have obsessive thoughts.But even if there were a Men's Health section (perhaps with a slim book on prostate cancer and another on bodybuilding) you would be unlikely to find a book talking about the way men are sucked into a "toxic triangle" of unhealthy behaviors -- because the assumption is that men are perfectly fine with their eating, their drinking, and even their overthinking. And, well, hmm, maybe they are, but maybe that's because no one's writing books scolding them about it.

If you do a Google search for "men who" and "too much" you find the classic book Men Who Love Too Much and a parody article "Men Who Love Hummels Too Much." But if you do the same search with "women," you find that women also love too much, but in addition they think too much, date too much, exercise too much, and plain old DO too much.

Of course the reason is not that women are more flawed than men -- and no one really thinks that -- but that women are more likely to buy self-help books. And Eating, Drinking, Overthinking will probably help a lot of women who will be, as I was, intrigued by the linking of these behaviors.

Nevertheless, it's awfully cynical to market a book to women because they're more likely to buy it if it's exclusively about them, when in fact the book describes universal problems.

Oh, well, maybe I'm overthinking.

Sunday, January 7, 2007

Useful Self-Deception

I'm about a third of the way through a novel I've been writing for four months or so, and over the past few weeks the work ground to a halt. Part of the reason for this was a home renovation project we've been doing, and part was the holidays--but the fact was, I'd been kidding myself about the real reason, which is subtler, and is actually relevant to the work itself.

There comes a time in any creative project when you've got to face what it is you're actually doing, and the consequences of doing it. You might be inspired by certain details, characters, or themes, and this might propel you quite some distance--but at some point, you have to face the music. In my case, I had come to a point in the plot of my book when I had to decide if what I was writing was a work of realism, or something else entirely.

If you'd asked me this four months ago, I would have answered promptly: it's something else. But nobody asked me, least of all myself. Until this morning, when I sat down to write after a several weeks' slump, and realized that I couldn't write the next sentence without answering the question.

It was easy. I answered it and moved on, with a renewed sense of purpose, and the book is back on track.

Why couldn't I have asked myself this question four months ago, or even last month, before my slump? The fact is, I didn't realize it was there to ask. I needed the bulwark of the first hundred or so pages to take the leap of faith that would deliver me to the rest. I was engaged in four months of useful self-deception, to ready myself to know what I was doing.

Writing, I think, is often a process of useful self-deception, like the cartoon coyote's gravity-defying pause before he plunges at last into the canyon. You have to look deeply into some parts of yourself, while denying the existence of other, even more vital, parts. It's no wonder so many of us are drunks.

There comes a time in any creative project when you've got to face what it is you're actually doing, and the consequences of doing it. You might be inspired by certain details, characters, or themes, and this might propel you quite some distance--but at some point, you have to face the music. In my case, I had come to a point in the plot of my book when I had to decide if what I was writing was a work of realism, or something else entirely.

If you'd asked me this four months ago, I would have answered promptly: it's something else. But nobody asked me, least of all myself. Until this morning, when I sat down to write after a several weeks' slump, and realized that I couldn't write the next sentence without answering the question.

It was easy. I answered it and moved on, with a renewed sense of purpose, and the book is back on track.

Why couldn't I have asked myself this question four months ago, or even last month, before my slump? The fact is, I didn't realize it was there to ask. I needed the bulwark of the first hundred or so pages to take the leap of faith that would deliver me to the rest. I was engaged in four months of useful self-deception, to ready myself to know what I was doing.

Writing, I think, is often a process of useful self-deception, like the cartoon coyote's gravity-defying pause before he plunges at last into the canyon. You have to look deeply into some parts of yourself, while denying the existence of other, even more vital, parts. It's no wonder so many of us are drunks.

Saturday, January 6, 2007

Global Warming Haiku

Came across this by the Japanese poet Basho today... so apt...

the first snow

just enough to bend

the daffodil leaves

Friday, January 5, 2007

A Couple of Long Poems by Ed Skoog

Why, check it out: new long poems by Ward Six chum Ed Skoog. A sample, from "Mister Skylight":

Read the rest on the online magazine Bedazzler.

I had forgotten that I had forgotten. I

had one hand in one century's big finish,

a new kind of metal, a bionic art:

it's a story my mother tells, thinking

of the wrong boy. She is old now.

And when my children yet unborn, die,

these stories will be forgotten,

like umbrellas in the coat check.

Read the rest on the online magazine Bedazzler.

Best American Comics

We're pretty faithful readers of the Best American Anthology Series, particularly the fiction one. And though this year's fiction is good (and is edited by our former teacher Ann Patchett), I don't think there's been a book in this series in ten years that's anywhere near as good as the new Best American Comics. There's something going on with comics these days--they have an energy, an aesthetic and moral vitality, that reminds me of the way short stories felt in the eighties. A sense not merely of skilled practitioners working in isolation from one another (which is true of any era), but of a unified, yet varied, vision, a community with a shared understanding of the world.

We're pretty faithful readers of the Best American Anthology Series, particularly the fiction one. And though this year's fiction is good (and is edited by our former teacher Ann Patchett), I don't think there's been a book in this series in ten years that's anywhere near as good as the new Best American Comics. There's something going on with comics these days--they have an energy, an aesthetic and moral vitality, that reminds me of the way short stories felt in the eighties. A sense not merely of skilled practitioners working in isolation from one another (which is true of any era), but of a unified, yet varied, vision, a community with a shared understanding of the world.

Frankly, it makes me wish I could draw. A few standouts in the book are Lilli Carré, whom I'd not heard of before this book (that's her stuff on the right, there, and also on the cover of the anthology)...also David Heatley, with his portrait of his father...the always reliable Lynda Barry...and the Beckett-like minimalist weirdness of Anders Nilson, whom I can't seem to find an adequate link for.

Anyway, this is a terrific book, a snapshot of a genre whose moment has come. Fiction writers, pay attention to the cartoonists. We could use some of their mojo.

Thursday, January 4, 2007

Indie Meets Lit

I recently got my hands on a galley of Jonathan Lethem's forthcoming novel. (This post isn't a review of it, but for the record, I don't think it's his best stuff. Like all of his books, however, it's an enjoyable read, very smart and funny, and if you liked the style of As She Climbed Across The Table and Girl In Landscape, you'll dig it.) The book is about the short life of a nineties rock band, and at one point there's a brief quotation from a song by the New-Zealand-based indie group The Verlaines.

I have to confess that this moment kind of broke my heart, and there are many others like it. Indeed, one character has a mix tape of New Zealand bands stuck in the cassette deck of his car, and though Lethem never names those bands, I can promise you that I know every single one of them (The Clean, The Bats, Look Blue Go Purple, etc.) Why did these references drive me to despair? It isn't Lethem's fault. It's indie-rock's fault.

When I'm not writing or teaching, I have a hobby on the side, writing and recording music, for fun. And while I like all kinds of music now, I came of age as a musician in the late eighties indie scene, and listened to this music almost exclusively at the time. I still like it pretty well, but it meant something particular then; it was the soundtrack to white, middle-class alienation, an expression of interiority and a rejection of mass culture. It was insidery and cool to listen to.

But more importantly, indie turned the pop model inside out. Whereas pop made you feel like some little part of the world understood you at last, indie made you feel like you were the only person in the world who understood it. Part of its charm was the way it allowed you to think, while listening to it, that all the other people who had never heard of it were idiots. Never was this more bluntly expressed than in Kurt Cobain's liner notes to Incesticide:

Oh no! The idiots have discovered us! Run for your lives!

I don't think many people, reading a piece of contemporary literature, would cringe upon encountering a reference to, say, Bob Dylan. Dylan, by his very nature, belongs to everyone. He rose to fame during an era in which the most popular music was often the most accomplished; the counterculture Dylan helped create eventually became a part of mass culture. Not so with indie rock. You can't start a revolution by looking at your navel, shapely as your navel may be. The bands that survived the era have evolved, become art-rock mainstays, are no longer "indie"; indie itself is basically dead.

The weird thing about Lethem's book is that, unlike books that use sixties counterculture as their setting, it works better if you don't know anything about its cultural context, and instead treat it as a self-contained world, like the one in Girl In Landscape. For my part, though, alas: I know too much.

I have to confess that this moment kind of broke my heart, and there are many others like it. Indeed, one character has a mix tape of New Zealand bands stuck in the cassette deck of his car, and though Lethem never names those bands, I can promise you that I know every single one of them (The Clean, The Bats, Look Blue Go Purple, etc.) Why did these references drive me to despair? It isn't Lethem's fault. It's indie-rock's fault.

When I'm not writing or teaching, I have a hobby on the side, writing and recording music, for fun. And while I like all kinds of music now, I came of age as a musician in the late eighties indie scene, and listened to this music almost exclusively at the time. I still like it pretty well, but it meant something particular then; it was the soundtrack to white, middle-class alienation, an expression of interiority and a rejection of mass culture. It was insidery and cool to listen to.

But more importantly, indie turned the pop model inside out. Whereas pop made you feel like some little part of the world understood you at last, indie made you feel like you were the only person in the world who understood it. Part of its charm was the way it allowed you to think, while listening to it, that all the other people who had never heard of it were idiots. Never was this more bluntly expressed than in Kurt Cobain's liner notes to Incesticide:

At this point I have a request for our fans. if any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us - leave us the fuck alone! Don't come to our shows and don't buy our records.

Oh no! The idiots have discovered us! Run for your lives!

I don't think many people, reading a piece of contemporary literature, would cringe upon encountering a reference to, say, Bob Dylan. Dylan, by his very nature, belongs to everyone. He rose to fame during an era in which the most popular music was often the most accomplished; the counterculture Dylan helped create eventually became a part of mass culture. Not so with indie rock. You can't start a revolution by looking at your navel, shapely as your navel may be. The bands that survived the era have evolved, become art-rock mainstays, are no longer "indie"; indie itself is basically dead.

The weird thing about Lethem's book is that, unlike books that use sixties counterculture as their setting, it works better if you don't know anything about its cultural context, and instead treat it as a self-contained world, like the one in Girl In Landscape. For my part, though, alas: I know too much.

Book mystery

This morning I was thinking about the different names for the male organ and remembered when I first encountered the word "prick." I was about twelve, in the children's section of the public library, reading a book about a British boys' school. What stuck in my mind is a vivid scene in which some boys are holding a race in the bathroom, naked, trying to see how far they can carry a slipper on their "prick."

Though now it occurs to me that the setting might not have been Britain at all, and the word might have been "peter."

I associate this memory very strongly with the Newbery awards section of that library, but I've scanned through the lists of Newbery winners and none seems to be this book. In those days, though, I was likely to sneak books from the adult section and take them back to the children's where I could read them out of eyeshot of the vigilant librarians.

Does this ring a bell for anyone?

Though now it occurs to me that the setting might not have been Britain at all, and the word might have been "peter."

I associate this memory very strongly with the Newbery awards section of that library, but I've scanned through the lists of Newbery winners and none seems to be this book. In those days, though, I was likely to sneak books from the adult section and take them back to the children's where I could read them out of eyeshot of the vigilant librarians.

Does this ring a bell for anyone?

Wednesday, January 3, 2007

William Blake, from 2007

In my campaign to read more contemporary fiction by women (I'm trying to find out if it really is all chick-lit these days) I've come across Apprentice to the Flower Poet Z. by Deborah Weinstein. I'm only about half-way through so far, so I'll hold my thoughts on it for the moment, but because it's about the world of contemporary poetry it got me feeling that maybe I should be reading more poetry, too. So I hauled out my Norton Anthology of British Literature, Vol. 2, and opened it at the beginning: William Blake. (I can't believe there's a whole volume before Blake!)

I had remembered Blake as a wild-haired mystic all about murdering infants in their cradles. But what struck me on this reading, maybe because of the particular poem I turned to ("Visions of the Daughters of Albion") or maybe because of the times we're living in, was his sense of scientific frustration.

He goes on. I'm always aware of the tendency to impose one's biases on poetry, but surely -- isn't Blake about to just explode with the desire to know all the things that science is about to discover in the next hundred years or so?